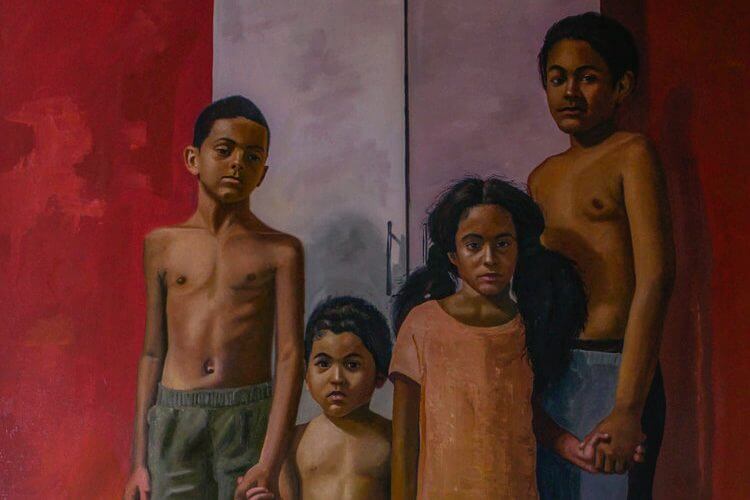

Above: The Future and Its Circumstances, Oil on canvas, 2017 by Raelis Vasquez. All images courtesy of the artist.

This past winter in Chicago seemed as if it would never end. Days upon days of dreary colorless cold plagued the region and left its residents to search for warmth in rather creative ways. Admittedly, both my search for heat and a thirst for fresher approaches to black figurative art lead me to the work of Raelis Vasquez. Redundant saturated images of black and brown people painted on canvases have been virally circulating on the internet over the last few years. Vasquez’s paintings on display at a local gallery in the Pilsen Chicago Art District cut through the misery of the cold weather and offered something nuanced and thought-provoking. I attended the opening hoping social media images of the artist’s work would live up to their allure when viewed in person. I was not disappointed. The young, ambitious, and incredibly focused painter’s work stood out, leaping from its co-exhibitors, causing large puddles of viewers to gather the entire evening.

As spring slowly, and reluctantly crept in, I was invited by Vasquez to view his work at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) 2018, Senior Show. His canvases were quarantined into a small space, and though there were only two of Vasquez’s paintings hung, the power of these images had transformed the area into a one-man show. A style that had been incubating during his lifetime had come to the surface, exposing the influences of his homeland — The Dominican Republic, and his current state as an immigrant of African descent, living in The United States.

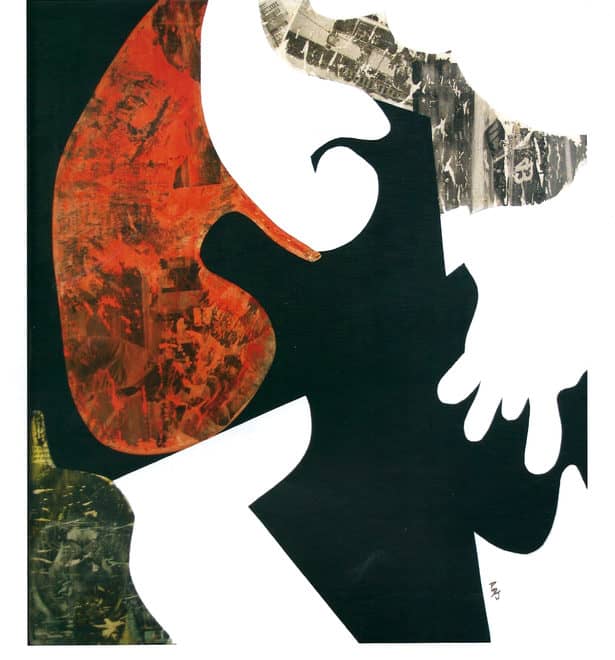

Above: En Las Mañanas (In The Mornings), 2018. Oil on Canvas by Raelis Vasquez.

With the recent focus on black figurative painters like Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Whiley, and Amy Sherald, the terms representation and racial/cultural identity have been tossed about ad nauseum in contemporary art spheres. Vasquez adds complex topics within themes of immigration to the discussions of blackness and racial identity in the United States discussions that have often been siloed within an African American context.

“I started painting, about eight years ago, but I began drawing soon after I came from the Caribbean. I was listening to someone recently say, ‘There is no reason to be creative unless you are trying to solve a problem,.’ So, while I was in growing up in the Dominican Republic, I was there, I was present, it was familiar. When I came here, I experienced immigration—trauma, that’s something that you don’t necessarily recover from,” Vasquez said to me, explain why immigration is are a recurring theme of his body of work. “Saying that it was hard would be like saying nothing, because, (as an immigrant) you leave your family behind. My Father left his family, his siblings, his parents, his job. There (Dominican Republic), he was an English teacher, but when he came here, he worked two factory jobs. I would rarely see my father the first couple of years we came here because he was working all the time, trying to get us out of where we were. There was ten of us in a one-bedroom apartment— a lot of people. I was seven, so it was weird. I can remember that time in my life better than I can remember my teens.”

Above: Untitled, 2018, Oil on Canvas by Raelis Vasquez.

Vasquez was born in The Dominican Republic and moved to New Jersey with immediate, and extended family members in 2002. The new, strange, and crowded environment soon changed as his family worked tirelessly to move into a large house in a better neighborhood. He credits his father for instilling the work ethic he practices now, which includes spending most of his time working in his home studio. I visited his studio a few times while witnessing him work on several paintings at a time. Most of Vasquez’s paintings are large-scale, almost life-size images that capture the interiority of the depicted subjects while displaying emotional narratives. The work ranges from traditional portraiture to contemporary genre scenes that represent people of color with multiple identities such as black, immigrant, mulatto, Afro-Latinx, and Latinx, all pressing against traditional concepts of what it means to be American.

“I’m interested in investigating immigration, but also the lack of representation of people of color. That’s my true investment. Why aren’t we represented? What does it do when you aren’t represented? It’s obvious what it does.” The painter often engages with work of Junot Diaz, a Dominican born author, and cultural theorist. “Junot Diaz wrote this brief article about vampires, and how vampires can’t see their reflection in the mirror. He talked about this theory that monsters can’t see themselves in the mirror. So, if you want to make someone a monster, you deny them of seeing any positive reflection of themselves on a cultural level. So yes, you can say that I’m doing representative work to describe the type of work I’m doing, but it’s more about me including these people. What happens when you say something exists, something is here, something is valuable? When it comes to the figures that I paint, they are all people that I know, and that’s important to me. I’m thinking about when I first went to museums, like when I was first old enough to take the train to New York City, and visit the museums, and what happened when I didn’t see myself reflected. So, I’m a young boy, and I’m not seeing myself reflected in any of the paintings that I was looking at. So, now as an artist, I’m trying to create a mirror, if you will. Right now, I’m working with scenes, so the subjects often aren’t aware of the viewer, but lately, I’ve been working on some pieces where the subject is very aware of the viewer.”

Above: Portrait of Seth Lawrence, 2018, oil on Canvas by Raelis Vasquez.

Vasquez’s work primarily consists of portraiture. However, some of his more recent paintings are narrative genre scenes that position the complexities of the subject’s interiority within the visage. These scenes also engage with symbolic representations within a depicted environment, such as a living room, or a kitchen.

The two paintings that hung for The SAIC Senior Show consisted of the same subject, Vasquez’s best friend who he considers a brother, Seth. In a haunting composition entitled Even Inside, Seth is a solitary figure sitting at a kitchen table. His expression is heavily pensive, as he looks away from the viewer with large, dim eyes. Without looking at the time that is indicated on Seth’s watch, it is evident by the somber hues used throughout the scene, that this is late night or early morning scene. Seth is holding a large coffee mug while staring at nothing. The use of a black figure in a genre scene perhaps is innovative on its own, considering the representational disparities of the canon of Western art.

Above: Untitled, 2018, Oil on Canvas by Raelis Vasquez.

However, Vasquez, through his positioning of Seth, directs the viewer’s eyes to key objects in the space. With the placement of a bright-yellow bunch of bananas, a plastic bag, and a single mango atop a plastic tablecloth, Vasquez has transformed classical still life tropes to capsulated representations of his culture. “Every, Dominican house has a coffee pot like this,” he said, referring to the depicted steel coffee pot resting on the stove in the kitchen scene. “Well yeah, I can say the same about African-American houses, and my grandmother always had a huge bunch of bananas on the kitchen table that was always covered in a plastic tablecloth.” I said as we both laughed “Yeah, it’s just black” Vasquez said. The varied symbolic representations of blackness in Vasquez’s painted environments transcends static, one-dimensional concepts of representation by presenting multiple narratives simultaneously; the bananas also tell a story

Vasquez’s everyday scenes of domesticity, depict subjects that are both engaged in a narrative but are also confronting the gaze of the viewer. There is a tension between the subjects of the images and the viewer, many of the figures seem to be disrupted by the external gaze, peering out as if they are asking “What are you looking at?”

Above: Portrait of Seth Lawrence, 2018, oil on Canvas by Raelis Vasquez.

“Getting my figures to be in a state where it’s not their masks that define who they are is very important to me. It’s about being human, which is not what we pretend it is. As humans we are flawed. As an immigrant of African descent, you realize that how you approach the world is very different, you’re always trying to prove that you’re innocent. I’m also working with the histories between the Dominican and the United States and looking at how behind the predatory accounts of these places are these narratives of innocence, stories that have found some way to justify harming people. Showing vulnerability is significant to me, especially within the male figures. As men, we are conditioned to hiding our vulnerability, but as an artist, I gotta explore that state of being vulnerable.

Be it a portrait, or a domestic scene, Vasquez works to tease out concepts of identity, and what it means to him personally. As I looked at his works, I marveled at how well I can put myself, an African American, into his scenes of family life depicting Dominican sensibilities and culture. “That’s the beauty about the specific!” Vasquez exclaims as I recognize the familiarity of a scene of a little girl getting her tightly curled hair combed by her mother. “It’s the beauty of the specific that makes it global,” he said.