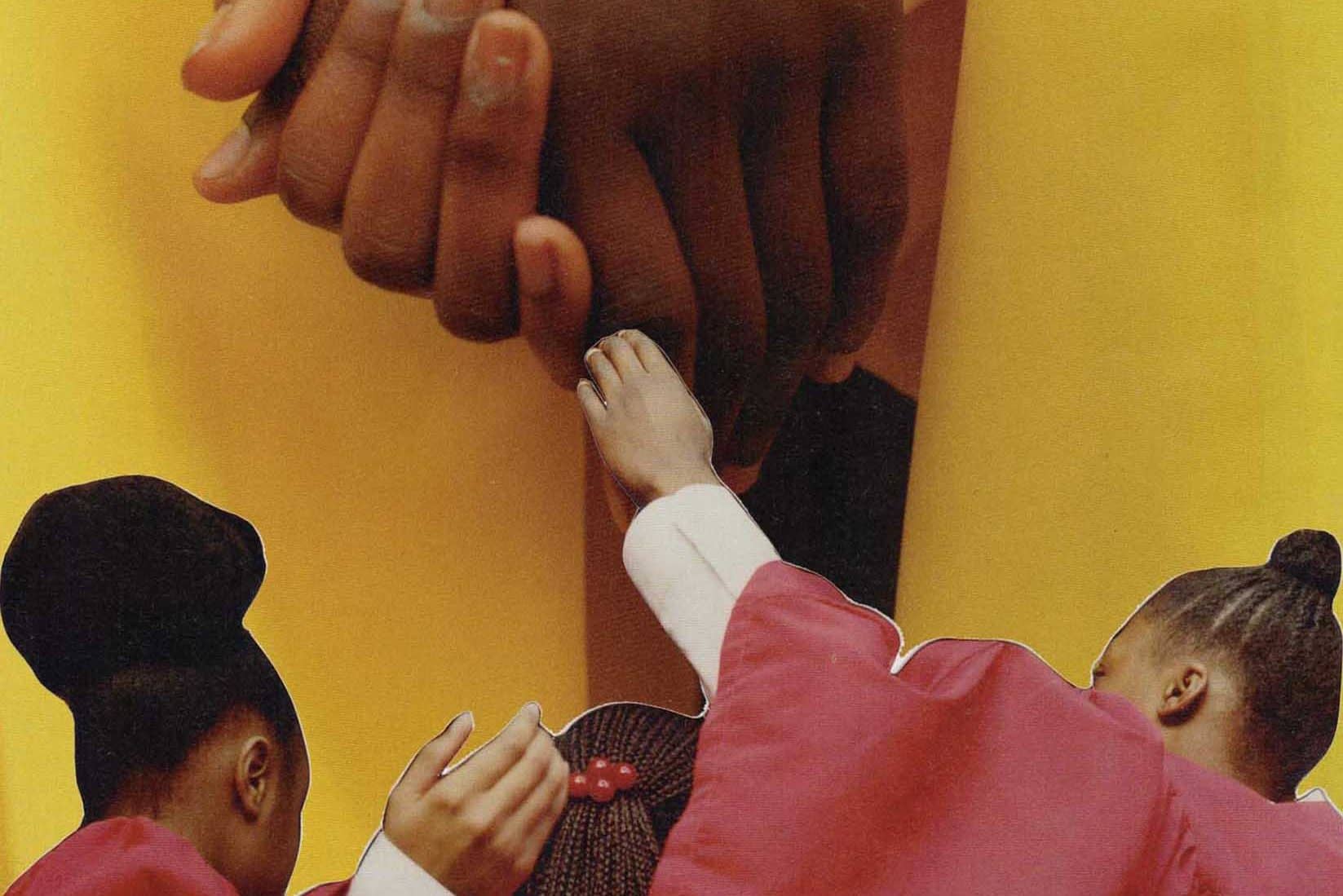

Above: We’ve Got The Whole World In Our Hands, Collage by Isaiah Lopez, 2018.

We see here the most subtle and perhaps the most profound trace of an extended engagement between two separate and distinct yet profoundly—even inextricably—related orders of meaning dependent precisely as much for their confrontation on relations of identity, manifested in the signifier, as on their relations of difference, manifested at the level of the signified. We bear witness here to a protracted argument over the nature of the sign itself[1]

But the truth is that their concern, its driving force, and hidden design, is the derangement of the memory, which determines, along with imagination, our only way to tame time.[2]

The plinths of the world are witnessing magic! Those imperial spectres that have long since been the plinths’ sole occupants are now subject to the powers of vanishing acts, conjurings and transformations. Of the plinth recently cleared of Cecil Rhodes, Gabi Ngcobo, curator of the 10th Berlin Biennale, asks, “What future possibility does this open space hold or enable us to foretell?” Ngcobo’s curatorial vision takes me home to Barbados, where the Horatio Nelson monument, in Heroes’ Square, Bridgetown, was turned yellow a few days before our independence anniversary.[3] Then moved across the water, to Georgetown, Guyana, we may see where the Queen Victoria monument was more recently turned red, soon after the Guyanese independence anniversary.[4] Being receptive to the play and violence at work in the transformations of such contested sites and materials is essential in approaching this year’s Biennale. Entitled “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” the works that have converged in Berlin are not simply concerned with replacing the plinth’s former individual set of values with another individual set of values. And it’s certainly not concerned with proposing solutions or making repairs. Faced with an irreparable stage, “We Don’t Need Another Hero” plays host to a talented troupe of tricksters and sorcerers, where the scar of such plinths – the surface of a historical debt and discontent – becomes a site for magical re-imaginings, alchemical salvaging, and illusion.

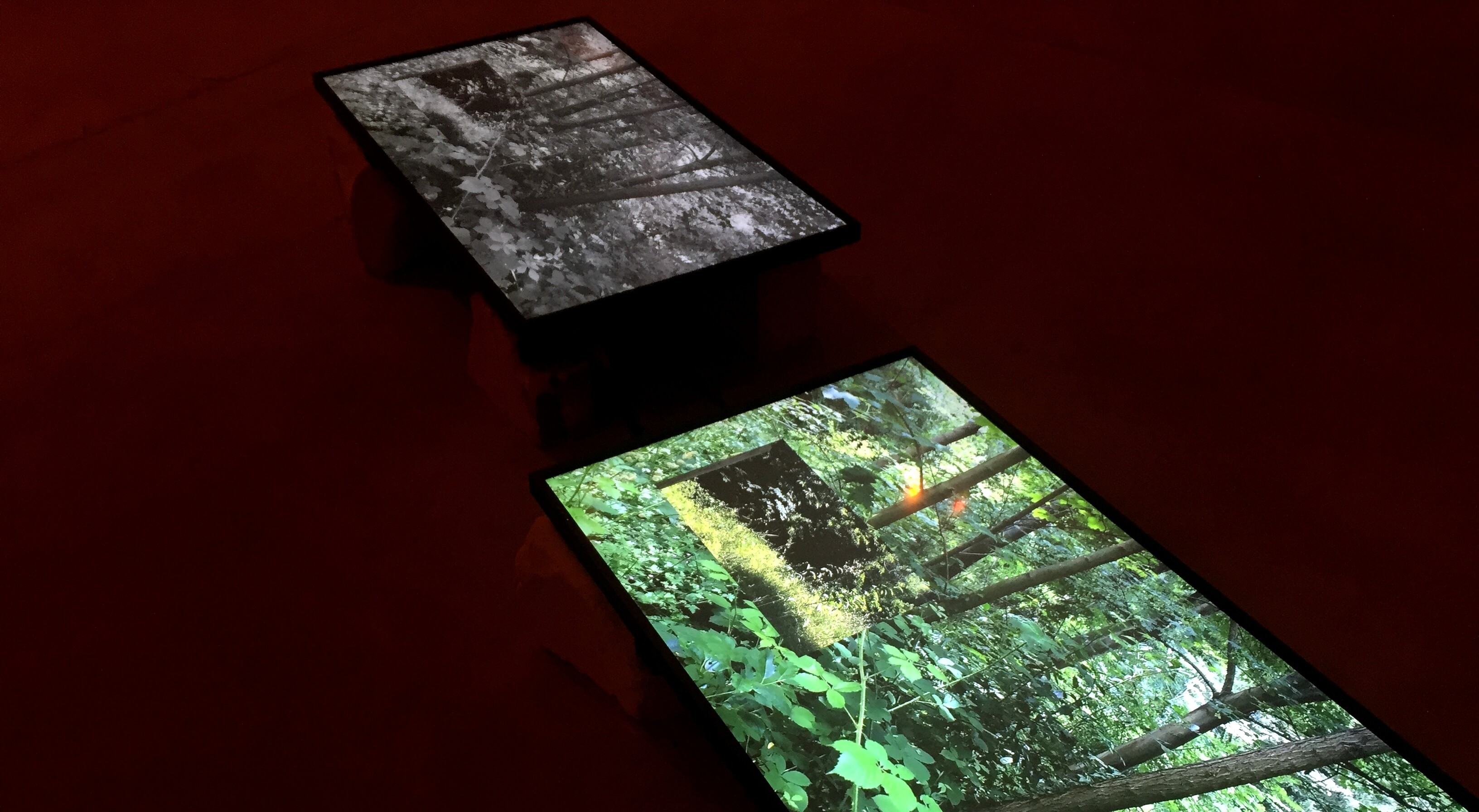

Above: Dineo Sheshee Bopape, ‘Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings],’ 2016–18, installation view, 10. Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Photo: Timo Ohler. All images are the intellectual property of their respective artists.

A blood orange crypt – a space between burial and prayer – lives as a room marred in perpetual twilight cracked by a rift in time. This space is a purgatory between a stagnant dystopic ruin and a lively vision of entropy; a promise of new life and worlds sprung from the reservoirs of magic and imagination. We are standing in Dineo Seshee Bopape’s ‘Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings]’ (2016-18) at the KW Institute, an installation of ruination that houses works by Jabu Arnell, Lachell Workman and Robert Rhee, among piles of bricks and columns, a cardboard wrecking ball, bucket fountains and videos, toned with the looping 1976 performance of Nina Simone’s ‘Feelings’. This is the crossroads from which the biennale’s curatorial vision seems to depart.

Above: Dineo Sheshee Bopape, ‘Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings],’ 2016–18, installation view. Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Of this stale wreckage, life glimmers in the windowed green of the video works; tablets or prophecies charged like seeds. Though dripping pitifully, with enough imagination, the bucket fountains resemble springs that beckon growth, healing, and prosperity. This is not a place of idyll or utopia by any means, where Nina Simone’s haunting broken howl chillingly assures us that the damage of this place is most certainly irreparable. These ruins – these scars – sit as a space for transfiguration, where a deranged memory must be actively revised and re-imagined again and again, until something of recovery hopefully may crawl out from the wreckage. The cracks of this site then become a “symbol of a conscious desire for life, a force springing forth, buoyant and plastic, fully engaged in the act of creation and capable of living in the midst of several times and several histories at once. Its capacity for sorcery and its ability to incite hallucination multiplies tenfold.”[5]

Let us, nonetheless, consult these ruins with their uncertain evidence, their extremely fragile monuments, their frequently incomplete, obliterated, or ambiguous archives.[6]

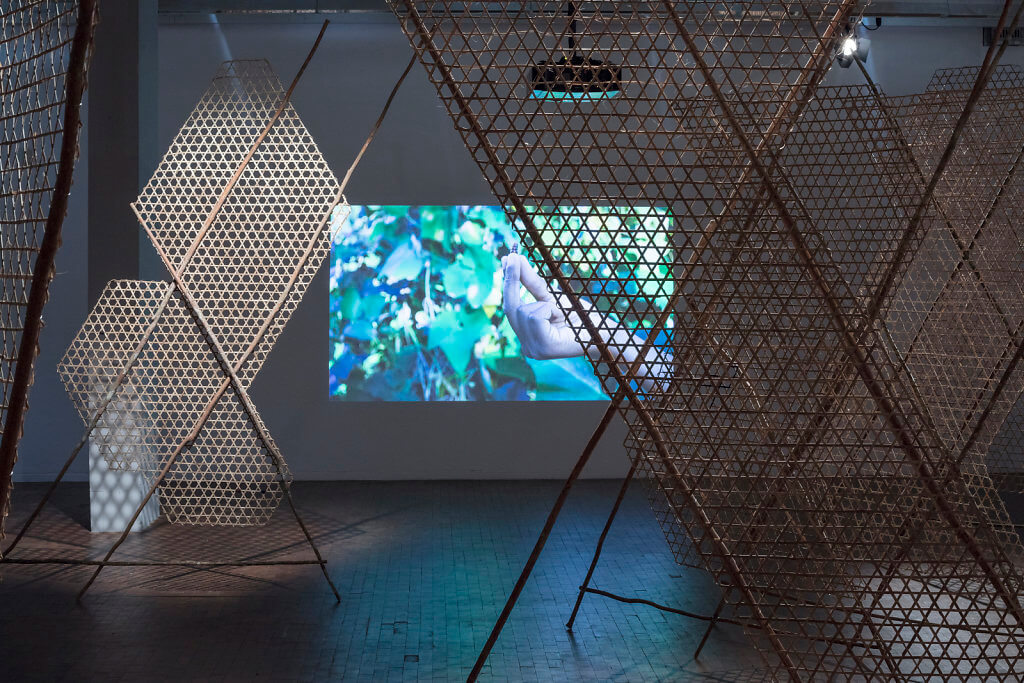

Above: Minia Biabiany, ‘Toli Toli,’ 2018, installation view, 10. Berlin Biennale, Akademie der Künste (Hanseatenweg), Berlin. Photo: Timo Ohler.

The act of conjuring new worlds, alternative systems of value and futures from the most subdued seeds of possibility is echoed in the works of Minia Biabiany and Firelei Báez at the Akademie der Künste (ADK). Biabiany’s ‘Toli Toli’ (2018), a video installation staged with hand-woven bamboo fish traps, is a childlike contemplation of butterfly chrysalises. The material process of bamboo weaving becomes a gesture branded in Biabiany’s body memory. Wrapping, braiding and weaving the air itself imitates the motions of the becoming chrysalis, which turns itself into a seed. Referring to a game where a pointing chrysalis would direct the player towards hidden worlds, like a living dousing rod, its instruction mirrors the internal promise of the chrysalis which, the narrator remarks, “draws the limits by projecting an elsewhere inside.” This inside ‘elsewhere’ remains an unborn reality, though its impending arrival betrays any expectations and comforts of any normative order.

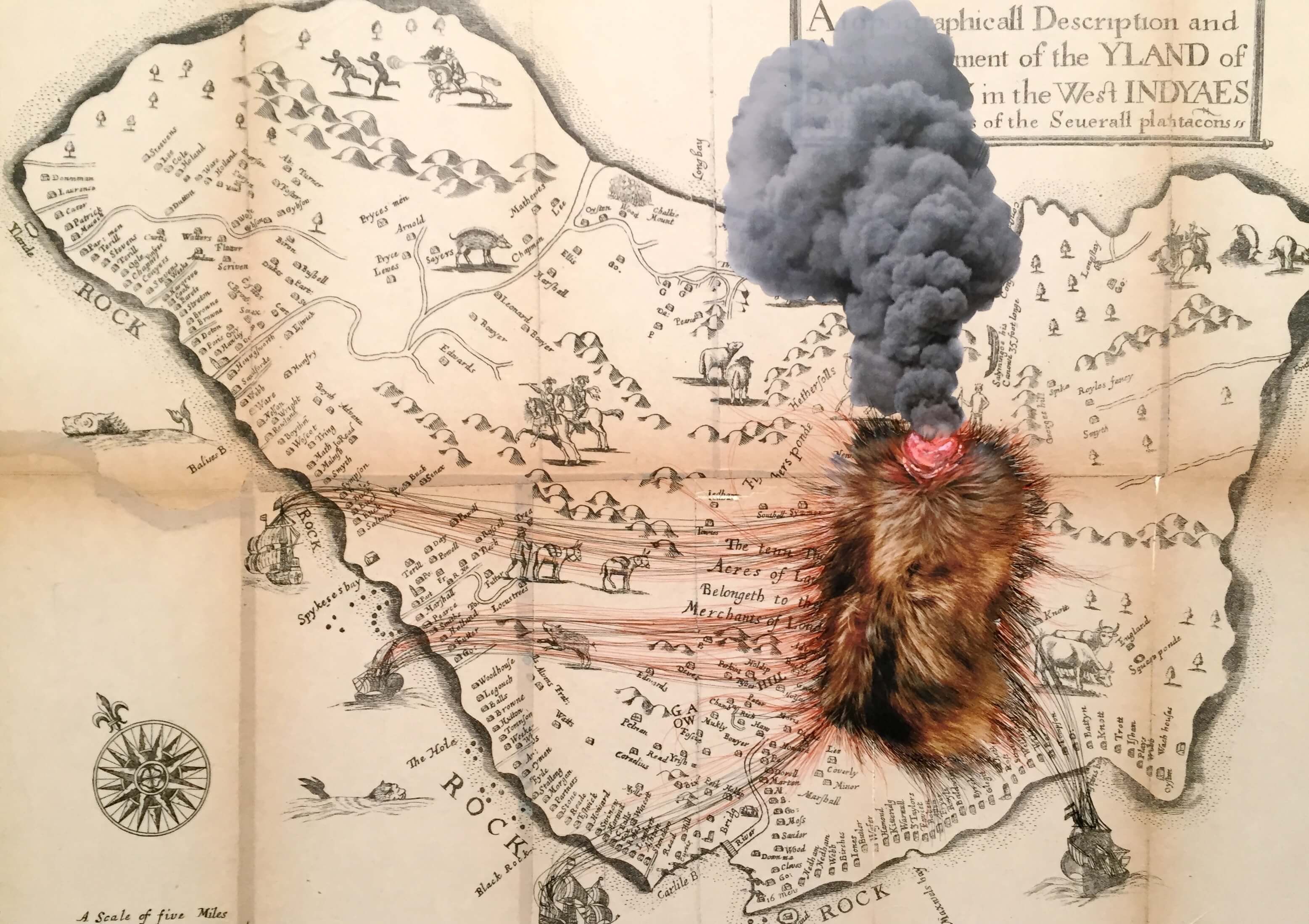

Above: Firelei Báez, ‘Those who would douse it (it does not disturb me to accept that there are places where my identity is obscure to me, and the fact that it amazes you does not mean I relinquish it),’ 2018, Detail view, Berlin Biennale, Akademie der Künste (Hanseatenweg), Berlin.

We can see the crowning head of this ‘elsewhere’ – this ‘otherwise’ – in the explosive interventions of Firelei Báez, as seen in the compilation, ‘Those who would douse it (it does not disturb me to accept that there are places where my identity is obscure to me, and the fact that it amazes you does not mean I relinquish it)’ (2018). In its very title, we are given a stern address as to Báez’s view of these gaps of obscurity in one’s history. With a foundation of deaccessioned pages, sourced from sugar refinery blueprints, biological tables, ledgers, old maps and such – artifacts of an ordered, recorded and known world – vibrant organic fires erupt from the surface. It is a playful emergence of undocumented memory exploding from within the documented archive, where such archives have functioned to preserve a singularly desired order and history, by way of selective repression of memory and subjecthood. From the seeds of a deranged memory, the works of Báez, Biabiany, and Bopape salvage new worlds through a depathologized reimagining of the more unsavoury qualities of their experiences, conditions and source materials “so that they are seen as a possible resource for political action rather than its antithesis.”[7]

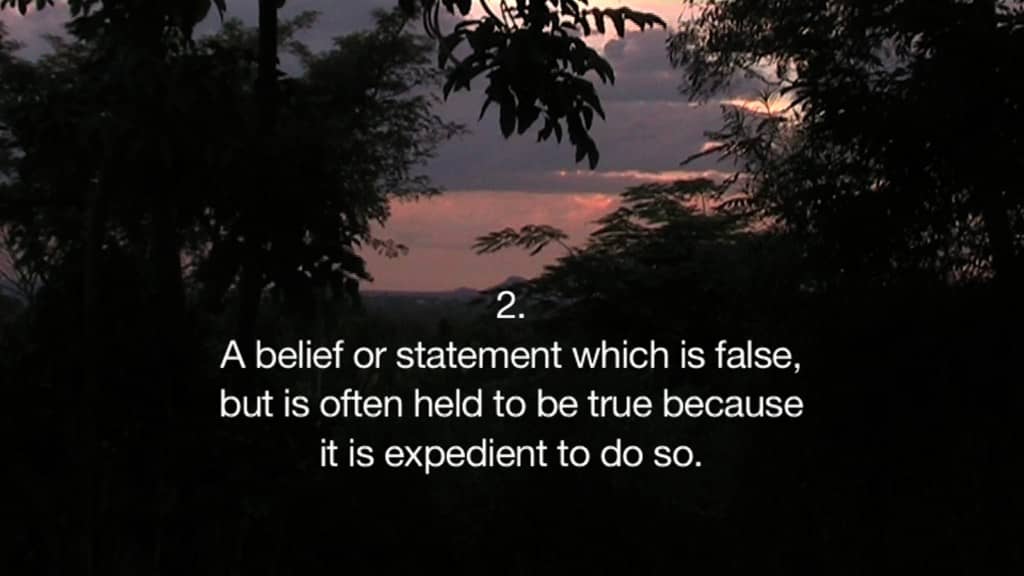

Above: Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, ‘Promised Lands,’ 2015, video still.

These revisions and responses to the materials, form and language of the confronted order emanate throughout the works and framing of the Biennale, allowing slippages and redistributions of power through “the recasting of an imposed nomenclature.”[8] The structure of language becomes malleable and its power dispersive. At the Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik (ZK/U), in Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa’s ‘Promised Lands’ (2015), the artist remarks on her father and brother’s decided (mis)pronunciation of ‘ponderosa’, rebranding it as ‘penderosa’, functioning as a deliberate playful reclamation of power from an established order and usage of language, around an object of personal mutual enjoyment. ‘Promised Lands’ unravels as an interrogation of the power held by fictional narratives in the social conditioning of our gazes. The power of language, its distribution and effect are held in an ongoing collective negotiation and compromise.

Destructure these facts, declare them void, replace them, reinvent their music: totality’s imagination is inexhaustible and always, in every form, wholly legitimate – that is, free of all legitimacy.[9]

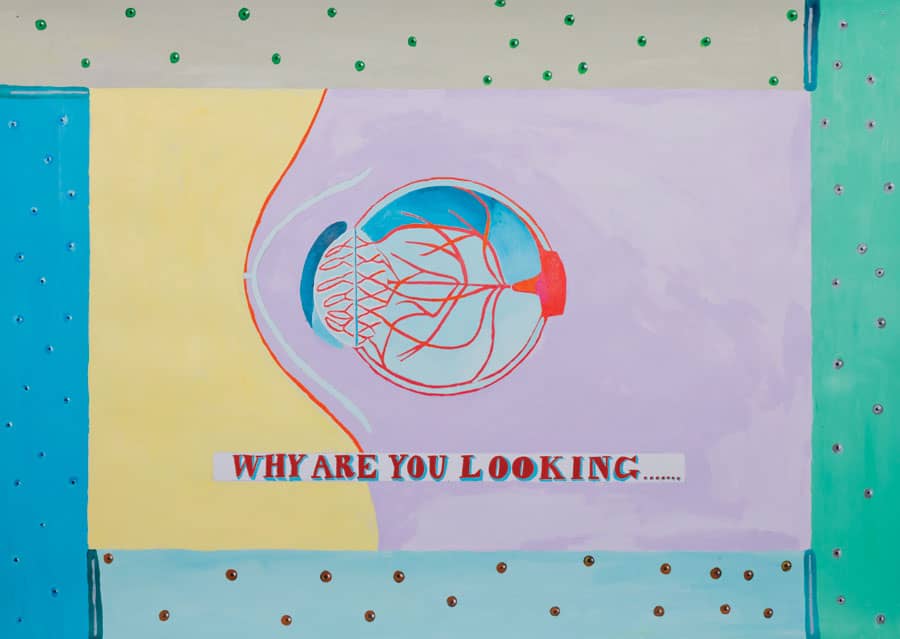

Above: Lubaina Himid, ‘Why Are You Looking?’ 2018. Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Hung across the sites of the Biennale, Lubaina Himid’s paintings in the series ‘Kangas from the Lost Sample Book’ (2011-12) read as opaque addresses, letters that recite themselves visually. Himid’s paintings borrow the visual language and intention of kangas, where greetings, prayers, warnings or critiques are gifted to the viewer. Like their source material, Himid’s paintings make use of a language that activates in appeal only to its desired receiver; if the message does not resonate, you are probably not being spoken to.

Above: Tony Cokes, ‘Evil.27.Selma,’ 2011, video stills.

Returning to the ZK/U, Tony Cokes’ basement installation, an underbelly of text-oriented videos, pulses like the frenzied sub-surface heartbeat of the biennale’s preoccupation with the risks of language. Cokes’ references and excerpts discuss how visual, oral and written media has been historically reframed and revised in service to such ends as war, torture, revolution and the repression of such, among others. For example, while Cokes’ ‘Black Celebration’ (1988) emancipates the actions of looting and rioting from conditions of criminality, Evil.16: Torture Musik (2011) remarks on the US military’s appropriation of disco music in its torture methods. Regardless of the moral or ethical inclinations of the wielders in question, language as a raw material, its deliberate usage and omission will always risk an exertion of power.

[T]hese texts were striving for disguise beneath the symbol, working to say without saying.[10]

The biennale’s concern with language, its elusive use of language, is a loaded decision responding to a history of inequity in critical engagement. The overshadowed readings and fascinations with an artist’s social context against the actual artistic merits of their work,[11] the malaise of disengagement that seems to affect those viewers and critics plagued with solipsism and a lack of empathic imagination, the cannibalistic nature of fantasy-ridden audiences; “We Don’t Need Another Hero” is carefully concerned with its self-image and the language around itself, simply because it does not feel inclined to bend to the expectations of its audiences. Elusion, manifesting as trickery, sleight of hand, processes of misdirection, obscurity and opacity, pushes viewers beyond the comfort of their expectations, all the while making room for new paths of relation to unearth themselves. It is a vision that responds to the systemic and institutional mishandlings, endangerments and abuses of an image and critical character, where vulnerable subjectivities are crunched into the fantasies of others and eaten alive.[12]

Above: Mario Pfeifer, ‘Again / Noch Einmal,’ 2018, installation view. Berlin Biennale, Akademie der Künste (Hanseatenweg). Photo: Timo Ohler.

The gaze of viewers, onlookers, and witnesses conditioned with desire, fear and prejudice has no capacity for justice, as demonstrated in Mario Pfeiffer’s ‘Again / Noch einmal’ (2018), at the ADK. Drawing from reservoirs of stereotype and strategically constructed narratives, vigilantes, and witnesses tied to an altercation at a supermarket in eastern Germany ultimately lead a young man to his death. Driven by a unity against an individual of difference, amplified by miscommunication via language barrier and latent prejudice buried in the psyches of those involved, the victim’s agency was taken away and the language and powers of the media sought to criminalise and demonise his very person. This exertion of power through very particular framings and language, through the abduction of another’s image, is an act of critical disengagement, whereby the object of disengagement is alienated, put out of place and made invisible, while any semblance of humanity is rendered incapable of being salvaged.

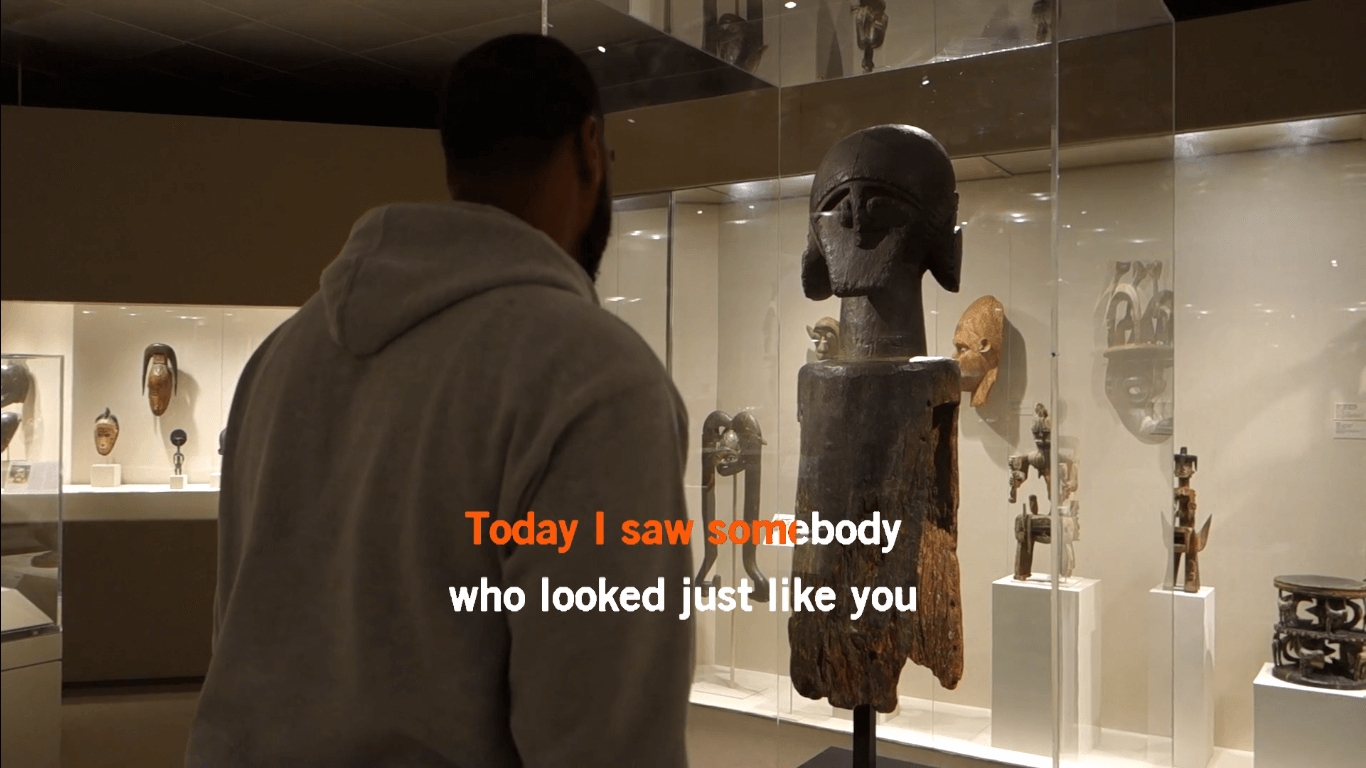

Above: Sondra Perry, ‘IT’S IN THE GAME ‘17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection,’ 2017, video still.

This condition of the abducted image also appears in Sondra Perry’s ‘IT’S IN THE GAME ‘17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection’ (2017). Perry’s video pairs the image of artifacts with the digital likenesses of youth basketball players, respectively stolen for museum display and video game production. Overlaid with a remixed ‘You are Everything’ by the Stylistics, ‘IT’S IN THE GAME’ playfully remarks on the changing nature and condition of personal and historic subjectivities. Scrolling through the avatars of his basketball teammates, remarking on his memories of them and walking through museum displays, the video’s protagonist is involved in an effort of memory, recalling and reflecting upon the integrity, origins, and passage of now dislodged and contested self-images.

You become the one who is questionable, the one whose biography becomes a testimony. Every bit of you can become a revelation. When you deviate from a straight line, it is the deviation that has to be explained. […] Some of these questions dislodge you from a body that you feel you reside in. Once you have been asked these questions, you wait for them; waiting to be dislodged changes your relation to the lodge.[13]

Above: Rodell Warner, ‘Family and Friends,’ 2017, installation view, “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not #14: I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not meets Speisekino : …and to think you had me believing that all this time…” curated by Christopher Cozier, 2018. Berlin Biennale, Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik, Berlin.

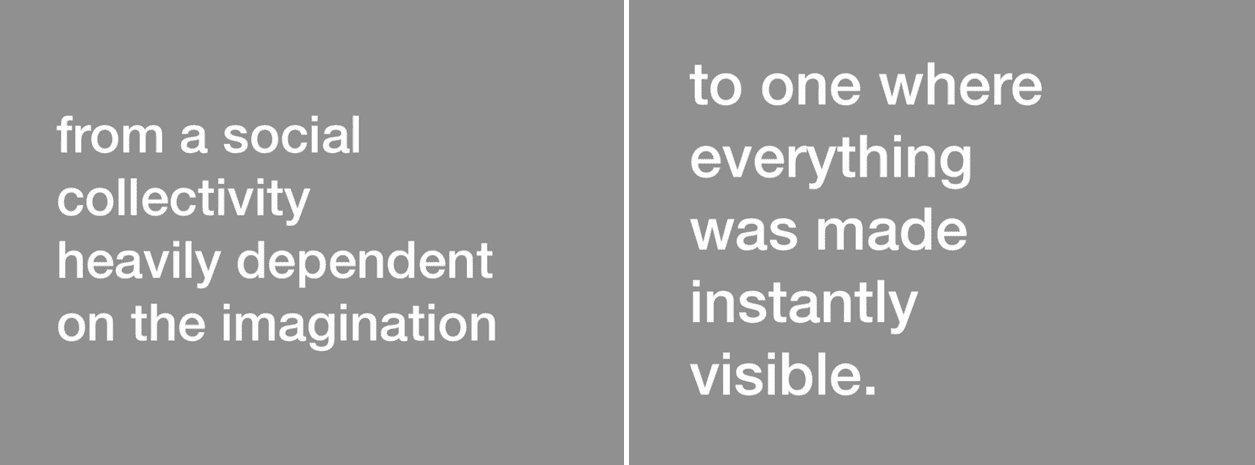

At this point, it’s necessary to turn to the biennale’s programming, “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not #14: I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not meets Speisekino : …and to think you had me believing that all this time…” an installation of video works at the ZK/U, curated by Christopher Cozier. With its tongue held, the event carefully discloses its nature, “Telling stories implies a distortion or fabrication that drifts or shifts too far away from facts. Perhaps, always in danger of arriving at truths.”[14] Without addressing the works in detail, Cozier’s experiment reads like a collision of stories and narratives that are not necessarily interested in meeting viewers halfway. As a whole, it asks, “What have you brought with you, behind those eyes of yours? Are you sure you want to bring more of the same? Are you sure you can rely on what you already think and know?” The type of magic to which I have been alluding and eluding is this delicate suspicion with which the Biennale may incite in its viewers. It is not magic concerned with any constructed illusion of itself but, rather, it is a subversion that contests the truth of a viewer’s conditioned sense of reality and knowledge. Can you trust what you know? Is your reality of reference, understanding, and relation truly a vision of clarity? The stories being told in “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not #14” are indeed suspicious of stories that have come before; in this sense, they are telling stories back. In this push-and-pull distortion of the fabric of reality, what truths will come about in the derangement of all that is known and trusted?

It might be that we cannot avoid questions: this is what it means to be in question. The political struggle then becomes: to find a better way of answering the questions, ways of questioning the questions, so that the world that makes some beings into questions becomes what we question.[15]

Refusing to give the people what they want, the elusive and opaque self-framing, posed by “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” reflects “a desire to avoid the exhaustion of having to insist just to exist.”[16] However, the Biennale should not be condemned to singular definitions of refusal. The careful selection and restraint of language around the self-image of the Biennale is a refusal only of the expectations viewers may have of it. Where it moves beyond refusal, the biennale’s language speaks in a refreshing tone of neutrality that addresses the critical concerns of the work, without derailing itself towards a troubling fascination with the artists’ social backgrounds. It is care and respect in language that does not want to dispose or pigeonhole, to exile the work to the context of where it was made, to deny the work of any entry into global discourses or narratives of humanity.

How come we have to refuse who we are for someone to be able to be able to identify with us? How come the audience can’t see themselves in that thing, whether or not it looks just like them or not? […] How can you see yourself in the other? That’s what it comes down to—empathy.[17]

Above: Okwui Okpokwasili, ‘Sitting on a Man’s Head,’ 2018, installation view, Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

This elusion in language is a test to the visitors of the Biennale. It does not want to infantilise its audience; it does not believe they are incapable of empathy or redemption. In the breaking of old orders and the conjuring of new worlds of relation, engagement with the future must be a collective action. Returning briefly to the KW Institute, the work of Okwui Okpokwasili, ‘Sitting on a Man’s Head’ (2018), has captivated this viewer, certainly more than expected. A blank square platform curtained off with plastic sheets, a space that breathes in the lightest inflection of air, ‘Sitting on a Man’s Head’ is a site for participation. Though empty on arrival, there was enough written encouragement to enter the space in participation. The written guide asks what its viewers and participants will contribute to space, establishing a site for a performative offering. Entering alone but soon followed by others, each of us presented something of ourselves between an anxiety and eagerness of gestures. This empty site – resembling a cleared plinth – reflects the stage to which “We Don’t Need Another Hero” invites us. Though what worlds may emerge from the opaque foundations of this plinth is uncertain, the future’s trajectory is decidedly not the sole responsibility of any particular individual or hero. Will the stories you bring keep this plinth intact or will they imagine cracks of possibility? Drawing the limits, together, of an ‘elsewhere’ inside, there is enough room on this plinth for everyone to imagine and visualise new paths of relation. It only requires that we make the step to participate and engage with one another’s humanity. [1] Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (NY: Oxford University Press, 1988). [2] Edouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (USA: University of Michigan Press, 2010). [3] Natasha Beckles, “Statue of Lord Nelson Defaced,” Nation News Barbados, accessed July 17, 2018, http://www.nationnews.com/nationnews/news/105621/statue-lord-nelson-defaced [4] Staff Reporter, “Queen Victoria Statue Defaced,” Guyana Chronicle, accessed July 17, 2018, https://guyanachronicle.com/2018/06/05/queen-victoria-statue-defaced [5] Achille Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason (NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 6. [6] Glissant, Poetics of Relation, p. 65. [7] Ann Cvetkovich, Depression: A Public Feeling (USA: Duke University Press, 2012), 2. [8] Coco Fusco & Christian Haye, “Wreaking Havoc on the Signified: David Hammons,” Frieze, accessed July 17, 2018, https://frieze.com/article/wreaking-havoc-signified [9] Glissant, Poetics of Relation, p.95. [10] Ibid., p. 68. [11] Fusco & Haye, Wreaking Havoc on the Signified [12] Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches by Audre Lorde (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007), 134-144. [13] Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (USA: Duke University Press, 2017), 115-135. [14] Berlin Biennale, “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not #14: I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not meets Speisekino: …and to think you had me believing that all this time…,” Berlin Biennale, accessed July 17, 2018, http://www.berlinbiennale.de/calendar/im-not-who-you-think-i-m-not-14-meets-speisekino [15] Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life, p.115-135. [16] Ibid, 115-135. [17] Arthur Jafa, interview by Antwaun Sargeant, Arthur Jafa and the Future of Black Cinema, Interview Magazine, January 11, 2017.