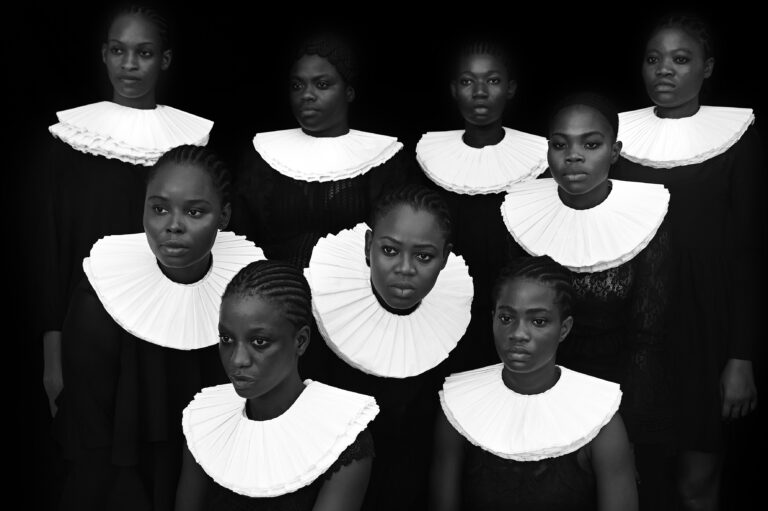

Above: work by T. Elliot Mansa. Photo by Angela N. Carroll.

In the afterlives of partus sequitur ventrem what does, what can, mothering mean for Black women, for Black people? What kind of mother/ing is it if one must always be prepared with knowledge of the possibility of the violence and quotidian death of one’s child? Is it mothering if one knows that one’s – child might be killed at any time in the hold, in the wake by the state no matter who wields the gun? Christina Sharpe – In the Wake: On Blackness and Being

Sites of mourning are marked by familiar objects; deflated balloons and toys strapped to light posts. Flowers and liquor bottles. Candles and candy. These indicators dot city landscapes and remind the community that a tragedy has occurred; life has been lost. Countless misfortunes are remembered with similar memorials, and much more go unsung. It is easy to overlook the memorials that proliferate the city.

What does it mean to grow accustomed to trauma? In In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, theorist Christina Sharpe describes the perpetuity of traumas African American communities experience with nautical and colonial terminology– the wake, the ship, and the hold. The conditions Sharpe articulates reveal devastating implications. Each new iteration of violence against Black bodies builds on preceding violence that ultimately trigger and reaggravate trauma on a cellular, physical and psychological level. Discoveries about the residual impact and long-term effects of racist violence on the body and psyche of African Americans are emerging. Still, I cannot help but wonder if Black identities are doomed to endure a perpetual state of mourning.

T. Elliott Mansa’s latest work, a series of untitled assemblages, is informed by the perpetuity and materialization of mourning. Previous works engaged figurative portraiture to explore familial and socioeconomic themes that incorporated Yoruba West African cosmologies and folklore. Mansa has exhibited at Prizm Art Fair, Art Africa Miami Art Fair, the David Castillo Gallery, and the African-American Museum of the Arts in Deland, Florida, among others. I visited Mansa’s studio in Tribeca, NY to build with him about the new collection and his transition from 2D portraiture into 3D assemblage.

The floor was buried under a mass of matte black and crimson structures. It was difficult to distinguish where one bundle of found objects ended and others began. Broken robots, remote-control trucks, baby dolls and plastic flora overflow strollers, activity jumpers, car seats, and other carriers. Mansa’s collages manufactured products into intimate and towering monuments that are whimsical and deeply troubling. I shared how intrigued I was by his work and the strange discomfort I felt being surrounded by it.

Above: Work by T. Elliot Mansa. Photo by Angela N. Carroll

T. Elliott Mansa: There’s this idea of memorializing someone as if their spirit is only passive. But if you look at the bottle trees in the south or live around Miami where you see a teddy bear on a door, but the idea that you can almost catch these spirits in the wind, or weaponize them to a degree. I think about that. I think about trying to make… there is a certain power in looking at the police shootings, and there is a powerlessness that I feel. So with this work, I am kind of creating these objects that do have power, they do have the power to stir up activity.

Angela Carroll: The work is definitely a powerful statement. In looking at your work, I thought a lot about the length of time it takes plastic to erode. Most of the sculptures you create are industrial objects that will outlast us all. Those objects are the foundation of your sculptures. Timeless totems.

TM: Yes. And I’m def aware that plastic is going to last. And that’s how this all feels, like a continuous state of mourning. The shootings are like a cycle, as soon as you go through one, another one happens. And there was a point when there were people that couldn’t speak to because you go through process of shock, protest, wanting to see someone arrested, but I remember a point where people were shot, but because it was too close [to another shooting] that person didn’t become a hashtag, the news cycle was too tight to be able to squeeze them in.

AC: Talk to me about the objects in your assemblages. Why are so many of the objects connected to children?

TM: As a child, people have that favorite teddy bear or blanket, and those are tied to transitional periods for them to move from being a toddler to moving across to adulthood. If you look at memorials, if there is an adult who dies, there will be teddy bears. They are very old ancestors. Sango was a king. That ability to become more. Whereas the young dead are young. A transitional object is like easing the transition from this world to the next. The more tragic the loss, the wider the memorial making is. I also feel like those memorials speak of being gone before your time. You don’t get memorials for natural deaths. Maybe if it’s a celebrity. Mostly its gun violence, interactions with the police, so there is a different stirring of different tragedies.

AC: What made you transition from 2D figurative portraiture into 3D sculptures?

TM: There are 3-Dimensional aspects to the 2D work. When I was doing collage it was increasingly becoming 3-dimensional because it was coming off the wall, and there were certain weaving and buckling, and then the paintings started getting really textural and 3-dimensional. I do come from a portraiture background, painting, drawing 2-dimensional work and I was aware that I was pushing myself further into the 3D realm, but it’s a great feeling to do something that you don’t know how to do, but you are learning. I found myself trying to figure out what I don’t do. I was trying to convert 2D inspiration to a 3D form. When you spoke earlier about the enki si sculptures and the nails and the attachment of packets and certain things, or strings, locks and ways to bind, fix, and hold, keep ill from coming to the people. I found that every element of combining things had a reason, so I think about suture cutting sowing stitching and think of ways to do that 2-dimensionally. It’s always in the back of my mind.

You have to destroy the kit that you came in with. Not everyone believes in this kind of pedagogy. The idea that you push yourself to transform or find new ways of working. I’m finding something that I can be excited about. The powerlessness that I felt I thought about art that was powerful. That was made for the sake of power, the sake of protection. Or honoring. So that was one of those things like trying to figure out how to do things. You have to look at what’s been done. It was just a matter of time for me to just move in the 3-dimensional realm.

Above: Detail from Untitled by T. Elliot Mansa. Photo by Angela N. Carroll.

AC: Each sculpture is supercharged, very weighted by the images that you juxtapose. The forms you create remind me of altars.

TM: I’m always thinking about finding visual langue to reference. Still unsure about how direct I want things to be. I’m always thinking about how do I pull the vernacular, the communal into space. That goes to your question about whether or not these things end up in the same space [as] memorials are. Does it become empty next to another memorial?

AC: Empty or activated?

TM: Right. That’s where the power of art happens. When you don’t run out of questions, it’s easy to be repetitive.