Paul Klee, best known for his idiosyncratic symbolism and ineffable shapes of color, influenced a generation of abstractionists in America that were all searching for a dual purpose: to make art that better reflected the emerging philosophy of existentialism, and create a world past what was commonly known as representational and true. At the Phillips Collection, a privately held museum in Washington, D.C., a new show demonstrates the different branches that 10 Americans: After Paul Klee has taken- with one, Norman Lewis, leading down a particularly dark path.

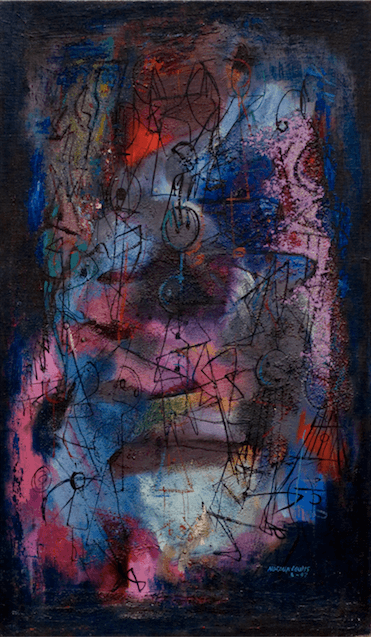

Lewis, the only artist of color in the collection of 10, imbues his canvas, “Untitled” (1947) with slashes of mars black that cut across a rough mindfield of sand, oil, and strategically placed visual detritus, likening itself to an alien landscape that looks out towards an aurora of many-colored lights. We see a sea-green flash in the middle, a deep and dusky rose madder ring around the center, with an overbearing night that envelopes it all. Throughout the drama of the background, lines, fine as calligraphy and with a foreshadowing nod towards the flow of graffiti, meander across the recreated night. They build their way up and back against the brightness of the middle and down towards the darkness of deep red and sienna, mixed in with sobering umber; and in that darkness, the only highlight is the grit that catches a glint from the external-the illuminating lamps above the piece.

Above: Untitled by Norman Lewis, 1947

Disavowing semantics is a vital element to Klee’s work, and creates the common thread that holds his artistic progeny together. The curator of this exhibition, Elsa Smithgall, worked to feature the latent elements of nature, anthropology, and polyphonic texture between Klee’s and the other artists’ work. Klee saw drawing as writing, as a means to reinterpret the anthropology behind pictorial writing: “[He sought to] liberate drawn lines from a descriptive function, [by practicing] a method of automatic writing… tapping his unconscious and giving visual expression to unpremeditated thoughts and feelings. “

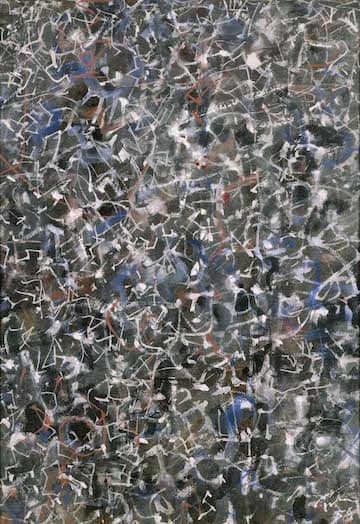

With Lewis, we see how his piece’s visual cues snugly fit between Mark Tobey’s “Night Flight” (1956) and Klee’s “Fig of the Oriental Theatre” (1934). Tobey’s deep experience with Chinese calligraphy and culture, along with Klee’s playful nod to non-Eurocentric art forms, complements Lewis’ outsider status from being an artist of color. Additionally, while other artists in the show have replicated the physical vitality of Klee’s brushstrokes and composition, it seems clear that Lewis (along with Tobey) pays more attention to the non-semantic, rhythmic aspects of Klee’s work.

Above: Night Flight (1956) by Mark Toby.

Above: Figure of the OrientalTheater (1934) Paul Klee.

Lewis continually showed love for his native Harlem, with his abstracted interpretations of African-American lifeforce, music, and culture; however, this also served to alienate the Eurocentric gaze of the post-war Abstract Expressionist audience. Instead of seeking commercial acceptance, Lewis, and fellow Harlemites Romare Bearden and Hale Woodruff started their own collective and taught painting techniques to the next generation of promising young artists. W.E.B. DuBois, in his 1926 speech The Criteria of Negro Art, foretold the continuation of the real and crippling “aesthetic limits placed upon black artists by the white establishment,” that will continue to“[demand]…racial prejudgment…[and]deliberately distort Truth and Justice…”; but Lewis still practiced in his unique style and point of view.

White friends who were accepted by that same establishment- such as Robert Motherwell (who also has a piece in the 10 Americans show)-shared Lewis’ interest in Marxism, philosophy, and art. Motherwell also encouraged his artistic following to branch out from Abstract Expressionism to Color Field Painting. Motherwell’s wife, Helen Frankenthaler, eventually mastered Color Field, and Lewis’ 10 Americans piece vaguely hints to that style through his hazy color application. There are no female artists displayed in 10 Americans, possibly to reflect their invisibility to the larger art world of that time; eventually, women connected to the abstract expressionist movement found some recognition for their work.

Above: Figure in Black (girl with stripes) 1947, Robert Motherwell.

However, white women’s ability to gain critical acceptance did not help Lewis in any material way. Throughout his life, Lewis struggled to find adequate gallery representation and clientele and died before he could see any meaningful commercial recognition. Today, a single untitled work of Norman Lewis, from 1956, is now estimated to be worth between $150,000-250,000.00.

Black Abstract Expressionists continue to struggle with breaking free from the fetishized idea of “Black Art,” that often focuses on the cursory representation of Black bodies in relief to white American culture. Some institutions are starting to take note of the still-extant socio-economic gap between Black males and females and white abstract artists of either gender; the Kemper Museum and National Museum of Women in the Arts both funded and hosted Magnetic Fields, the first major retrospective of Black (and female) Abstract Expressionists from the past 100 years. The real hope, though, is that one day, there will be more shows such as 10 Americans that will organically include contributing artists of different colors and genders on an equal footing to better-known pioneers of modern art.

10 Americans: After Paul Klee will continue at the Phillips Collection until May 6th.