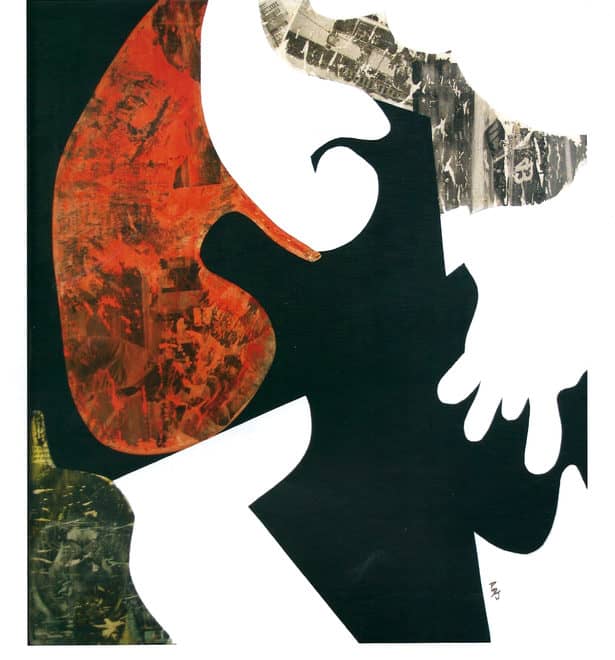

Above: Phillis Diane Jones, “Stan’s Dance,” 1968. Mixed media on canvas. Photo courtesy of N’namdi Fine Art and ArtSlant.

The 29th annual Porter Colloquium (named in honor of the late Dr. James Porter, the inaugural Dean of Art at Howard University) focused on the history and concepts of Abstract Expressionism; also, presenters explored ways in which Black artists use that style for self-determination in Eurocentric culture. The three-day event featured over 30 lectures by noted academic, artistic and curatorial members of the African Diaspora; and explored the need to reconcile the evolving concept of negritude with the free expression of Abstract art. Many presenters and audience members at the Colloquium also attended the Black Portraitures Conference at Harvard, which occurred just two weeks prior.

Some highlights from the Colloquium include:

Dr. Gregory N’namdi of the N’namdi Collection (HQ in Detroit, with satellite locations in Chicago and Miami), speaking on how he began his gallery and the many artists of color that mentored him along the way;

Ms. Kesha Bruce, fabric artist (based in Phoenix, AZ), describing the inspiration behind her works, which involved paying respect to her spiritual path and connection to her ancestors; and

Mr. Gregory Coates, painter, and sculptor (now living in Allentown, PA), discussing his travels overseas, and how he learned to grow from his beautiful mistakes.

Above: Dr. N’namdi. Photo by the author.

Dr. N’namdi’s interest in fine art started when he was still a psychology graduate student at Ohio State University, where he first made the “connection between art and [a] community’s mental health.” In 1968, he acquired his first collectible, a bold mixed media collage of acrylic and pattern entitled “Stan’s Dance,” which was created by artist Phyllis Dianne Jones. Even then, he focused on personal taste over perceived market value, paying a semester’s worth of tuition for the artist’s work.

Over time, he amassed a personal collection of over 250 pieces, with a distinct focus on Abstract Expressionist works by artists of color. Throughout Dr. N’namdi’s long career of collecting and curation, he cultivated relationships with the first wave of Black Abstract Expressionists in NY during the 60s and 70s; he emphasized that these creatives made the original distinction of ‘making,’ as opposed to ‘painting,’ paintings. During the 1980s, Dr. N’namdi started to teach his clientele the importance of patronizing Abstract, as opposed to cliched, interpretations of Black people and emotional expression. Over time, his efforts lead to a permanent shift in the Black art market within Detroit and minority–majority cities around the US. He continues his art outreach in his flagship gallery in Detroit, educating the public on the finer details of collecting for and selling to a high end, diverse market.

Above: Kesha Bruce, “The Sky Opened Up for Her,” 2016. Part of her ongoing “Weapons For Spiritual Warfare” series. Collaged fabric on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In contrast, Ms. Bruce’s presentation focused on how she saw art as a calling as opposed to merely an occupation. “At this point in my career,” she began, “I’m most interested in taking what I do best and doing it for my people… in a way that aligns with my core beliefs.”

The larger art market, she elaborated, does not embrace or nurture women of color. At the start of Bruce’s career, mainstream critics consistently labeled her art as “aggressive” because they did not have the ability or inclination to see her work past their preconceived notions of race and sex. More disturbingly, she talked about how she spent three years attending 25 art fairs in several different continents but saw less than 10 Black women artists selling work alongside her.

Bruce eventually found fulfillment by targeting her work to a niche market that can indeed identify with her message and process-Black women. Drawing inspiration from her female ancestors and the spirituality that she developed through her relationship with them, she devised a pictorial writing system that could create sentences on timing, place and her emotional state of being during work of art’s creation.

Bruce’s current practice involves spending weeks or months with each new piece: tearing up and dying fabric, painting over top of them, and following a specific, meditative process:

I like to think of [new ideas] visually, as floating above my head, and taking them out of the sky, bringing them down, and making them something physical… there’s signs, shapes, and colors that have specific meaning to me, and only to me!”

After Bruce finishes her one-on-one time with her creations, she releases them to the market and world, where they are free to take on a life of their own.

Additionally, sculptor Gregory Coates discussed how his experiences abroad helped influence the development of his work and philosophy. During the last 15 years, he completed multiple residencies in Japan and Europe, where he was commissioned to create site-specific public work. Coates used assigned sites and found materials to blend nature and history with plastic, metal and other by-products of industrialization. By using these scraps of metal, the artist is able to help the environment by reusing them in his artwork. When creating his artwork out of this metal, it’s likely that Coates uses welding techniques to ensure the metals are securely joined together. Joining metal together can be difficult as the metal needs to be on a flat surface, this is why many artists and welders use a welding shop bench to help them cut and join these pieces of metal together accurately. That would be helpful for artists to ensure they’re making accurate pieces of artwork. Additionally, scale, placement, and negative space became integral to the construction of the many outdoor pieces that he did outside of the U.S.

However, Coates took a significant detour in his land art practice to create smaller-scale works that reevaluated the host cultures’ (and his own) standards of perfection. Over the course of his practice in Germany and Japan, he observed a societal idiosyncrasy:

“There are places where failure is not tolerated. It’s success. And to throw at them a curve, I put my ‘failures’ on display… as evidence of my risk, struggle, and continuation.”

Above: One of the gridded pieces in Gregory Coates’ “Making Mistakes” series, 2008. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The ensuing series, “Making Mistakes,” spanned from 2005 to after 2008, using rejected watercolor paintings as a medium. Coates collected 1000 rejected works on paper, balled them up and arranged them in neat little grids; the repetition and scale of such an act are reminiscent of Zen philosophy and the Buddhist idea that creation is a necessary complement to destruction. Each piece of trash in the series is transformed into a treasured object through placement and context– and over time, those happy accidents helped to create a harmonious whole.

In closing, the conference organizer, Dr. Gwendolyn Everett (Associate Dean and Director of Howard University’s Gallery of Art) stressed the importance of discussing Black abstraction as a new form of liberation. In her eyes, there is a critical need for “new definitions… [that will help] rethink the ways we are interpreting” the world around us. Ultimately, Dr. Everett charged the academics and writers in attendance to publish, raise awareness, and host public forums on the future potential of Abstract art in African communities, as well as craft the terminology that will help define it. œAnd,” she added, “if nothing comes from the Porter [Colloquium] other then that, I think that would [make it] a success.”