Around 170 galleries and exhibitors displayed at the 12th annual EXPO Chicago fair, and only eight were African galleries. Five were from Cape Town, South Africa, three were from Johannesburg, and one, Rele Gallery, was from Lagos, Nigeria. Since African galleries represented less than 10% of the fair, South Africa’s significant presence begs the question: What does it mean for South Africa to represent the diverse landscape of Africa on a global stage?

Luckily, the South African galleries weren’t the only galleries showing art from African artists, yet most of the artworks from these galleries were from multiple countries. The Melrose Gallery from Johannesburg was an outlier, showing pieces from artists outside its country. It showed Papytsho Mafolo, a Congolese mixed media artist; Médéric Turay, a mixed media artist from Côte d’Ivoire; and Ayanda Mabulu, an acrylic painter from South Africa.

Logistical challenges, such as cost and space, make it difficult for Africa to have a strong showing at international fairs.

“There’s a barrier to entry in the U.S. for African galleries,” Craig Mark, director of the Melrose Gallery said, “in terms of the price of the art fairs, the enormous costs of shipping, and also in terms of the curatorial committees who decide on which artists and which barriers can show.”

South African galleries seemed to hold the responsibility for representing Africa. Participating in EXPO Chicago requires a $200-to-$300 non-refundable application fee, with booth rentals ranging from $16,500 for profiles to as much as $66,000 for galleries. Unfortunately, it makes sense that more galleries, which are from colonized African territories, weren’t present at EXPO Chicago.

Some galleries had multiple locations in Western art-hub cities like New York, Los Angeles, London and Paris. EBONY/CURATED, Gallery MOMO, Everard Read, Martin Art Projects, and Melrose Gallery were the South African galleries that showed art at EXPO this year. The South African galleries seemed to bear the responsibility of showcasing art from throughout continental Africa.

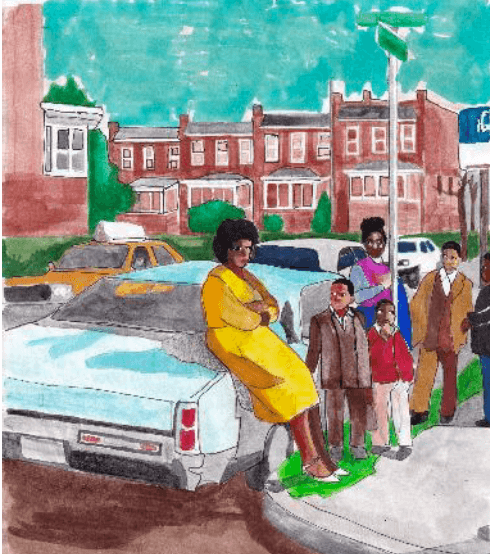

Made In Africa, by Ayanda Mabulu at Melrose Gallery, references Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeline. This piece allows the woman to speak for herself, a metaphor for African artists’ voices, with a focused, noble and dignified gaze. The piece uses the woman’s eyes and the texture of her skin, clothes and background to champion fluid self-determination from patriarchal and Western dominance.

When galleries have locations in African countries, the countries typically represented at Western art fairs are usually the same. Despite the diversity of thousands of cities in 54 African countries, the same few cities, considered Africa’s thriving art hubs—Lagos (Nigeria), Johannesburg, Accra (Ghana), Nairobi (Kenya), and Marrakech (Morocco)—consistently dominate at Western art fairs.

This trend reflects the colonial legacy. Galleries represented typically seem to be from former British colonies like South Africa or Nigeria, representing either themselves or different parts of West Africa. Against destabilizing conflicts, Anglophone Africa—South Africa, Nigeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana and others—seems to have infrastructural advantages after the “Scramble for Africa.”

The “scramble” or “partition” of Africa in the 19th century determined the present-day geopolitical map of African countries. Results from Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal, Germany and Spain’s conquest of Africa also determined the economic realities of these countries. To this day, economic factors have determined which stories, artists, and imperial reflections enter the Western art world.

“A lot of it has to do with the infrastructure, but also in terms of the capital that’s in a country, and what people prioritize in those countries,” director of MOMO Gallery in Johannesburg, Odysseus Shirindza, said. “South Africa is a very, very strange place, because somehow it sits within the developing country space, but also with the privileges of a first world.”

The modern world reflects how Africa has been undervalued and ignored historically. Even the focus on wanting Africa at fairs is Eurocentric, which shows the power imbalance of the Western markets. Even if Africa were to develop a stronger relationship with Asian markets, the first and third largest global art markets still would be Western.

Associating with the West has a greater material impact because of its significance in global art markets. The West’s success in the global art market is self-fulfilling to the extent that fine art’s display, in a white cube gallery theory, was designed and is practiced by Western institutions.

Ultimately, Western markets grant preferential treatment to African galleries with historical ties to British colonies, leaving Francophone African countries underrepresented at EXPO Chicago, although some artists were included. More representation of the diaspora at fairs like EXPO can help chosen artists financially, but it also can deepen the world’s awareness of how Africa sees itself.

Artists often seek recognition by exhibiting at international art fairs, but the artwork itself carries its own agency. Visibility in the Western art world does not necessarily grant an artist legitimacy. While financial opportunities remain accessible to only a select few, all Black artists share a sense of fellowship through the chance to witness and engage with new expressions emerging from the Afro-diaspora.

“We all share almost the same kind of story and struggles as Black people across the world,” Shirindza said. “I don’t think we can fix the whole entire system, but we can start the right conversations within our own community, for people to be able to relate with the work, and engage with it without feeling like they’re the outsider.”

Indigenous African representation is important for sharing individual postcolonial perspectives, which are single instruments in the orchestra that is Africa’s creative voice. According to page 42 of Art Net’s 2025 Intelligence report, contemporary and post-war art are the most lucrative categories. There may be untapped potential for ultra-contemporary African art to gain traction by reflecting Africa’s own destabilizing conflicts—just as Western postwar art reflected its time.