By Quincey Arrington

When Faith Ringgold is one of the earliest lessons you have ever learned, everyday African life in the U.S. or anywhere else can be a freedom unto flying. Ringgold passed over to the ancestor realm at the age of 93, leaving a legacy. We, the African American children she helped raise, had her longer than we had most, but it seems not long enough. Not because we do not wish her rest, but because there is a lithesome audacity in our gut that her work gave, which will miss its catalyst.

My first introduction to Ringgold was through her book Tar Beach (1990). In it, a young Cassie Louis Lightfoot tells a Harlem story about her family and friends enjoying an evening on the roof of their building. In the safety of communal love, Lightfoot’s imagination lives up to her name. The eight-year-old flies around the city claiming all that is below her wingspan.

Flying is a particular occupation of African Americans. Charles Page was the first person in the world to file a patent for a flying vessel. Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman to have a pilot’s license, was known for her institution-building spirit and daring flight technique. Mae Jameson inspired many who were to come after with aspirations of flying into space. However, Lightfoot’s reason for flying was simple: it’s for places you can go to no other way. For kids like me, she showed us that it was life with all its big and small parts, tragedy and ecstasy, hopes and disappointments, which send one to soar.

Lightfoot’s perspective resonates with Toni Morrison’s novel Tar Baby (1981), where she identifies life’s innate sufficiency. A moment without added glamour, great documentation or external forces. Yes, her father’s work was as sparce and dangerous. Yes, her mother’s work was as unending as her worries. Yes, tonight, there will be flying, feasting, resting, claiming and card playing in a city tamed by a Lightfoot gaze.

One of the greatest misconceptions about artists like Faith Ringgold (Betye Saar or Dindga McCannon) is that they received their recognition later in life, because Ringgold’s success was erroneously verified by the same principalities that tried to hinder her practice. Meanwhile, Ringgold was painting, quilting, protesting, sculpting, exhibiting, writing and raising children. It was my African American teachers in Chicago who introduced us to Tar Beach and Coretta Scott King who gave it an award. Our parents read us that book. They all answered our questions about parapets, quilts, flying. We are her inheritance.

So much so, that on a night of exhaustion from work, my momma witnessed her children climbing in through a window from our neighbor’s two-flat adjacent roof, back into our courtway building’s third-floor apartment. We danced on the roof for a few brief moments. I imagined I was flying. The darkness of the roof and night around us played its part as I tilted my head to the sky. Through the slits of tired almond eyes, momma at first thought she was dreaming as we giggled past her. Alarmed from her drowsy state, momma told us never to do it again out of concern for our safety, but we could tell she was so impressed and amused. We never went on Mr. Taylor’s roof, again, knowing we could never re-create that moment nor betray our momma’s grace.

When Mutha Ringgold’s retrospective exhibited at London’s Serpentine Galleries in 2019, I got on a plane to see it, not wanting to miss the opportunity. It was the culmination of a blessed encounter, where I saw the early planning of the exhibition at ACA Gallery, which would also lead to major exhibitions at the New Museum, Glenstone Museum, and Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, among other institutions. At the gallerist’s mercy, I walked into a room full of quilts and dolls I had never seen before. The room smelled of fresh rope and fabric coming from the perfectly preserved masterworks. It was such an overwhelming experience that, to my surprise, I cried when I left the gallery.

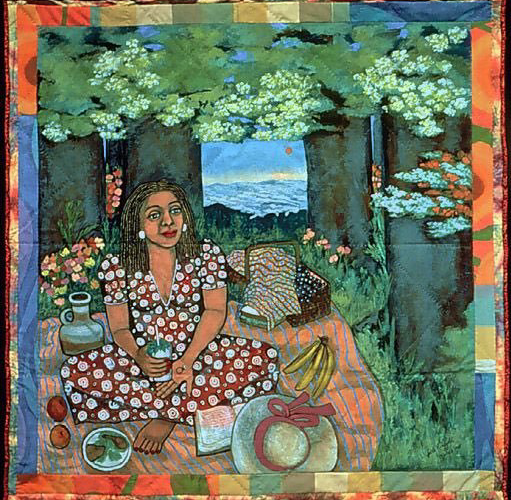

My hope was fulfilled at Serpentine when I saw the quilt that inspired the book, Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach (1988). It was safely behind glass and, to my surprise, surrounded by people who looked just like me. I talked to an auntie who was working museum security about all the African faces I saw in such an unlikely place. Auntie told me that there was a BBC special about the exhibition. Then, family showed up in droves.

We all had this look in our eyes as we examined the many interests of Ringgold’s career—the shock of our faces relaxing for flight. I have seen this look so many times when watching people view Ringgold’s art. It’s witnessing African feelings we all intimately know, imbuing color choices, painterly gestures, or even the consideration of weight, which is different than depth in a composition.

For instance, Ringgold’s weight often appears in her depiction of the body in relation to the background. Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach (1988) portrays an equality of the human figures seated at a table with the towering buildings in the background as well as the children laying on a mattress in relation their own rectangular roof in the foreground. The effect comes off consistently and thin like a wing.

In Black Light #11: US America Black (1969), countenances dominate the composition while blending with the background, making them unified and striking. Doing so also creates a floating feeling, but heavier like a buoy. Ringgold’s colors give on and with, in the words of Édouard Glissant, her respect to weight in the deep reds of this work. The tomatoey-blood and orangey-red hues filter the varying countenances of our people kissing, sleeping, wondering for skin, make-up and background while being punctuated by other colors like royal blue.

It’s a mastery of tonality in color blocking as well as contrast, shared by other artists like Lynette Yiadome Boakye, Kerry James Marshall, Nirit Takele and Derrick Adams, which creates more subtle transitions. This calm is only not reserved for just Anita Baker-soundtracked moments. Even in the work, another woman’s gleeful surprise is molded by the artist’s perfect love affair with calm subtlety. It is a sufficiency not easily shifted by surprise or contravening attempts.

Ringgold’s art practice is one that shows how home is vast but not daunting. For over seven decades, she showed us the art of her world and inspired us to make our own. It is more than enough.