Strada Gallery’s first exhibition in its new space, Embodied Spaces: The Body as Architecture, was curated by Paul Hill and Kimberlean Donis. The exhibit intended to draw parallels among anatomical, architectural and fashionable forms by curating artists whose work challenges standard movement throughout space and place.

On Friday, Sept. 8, Strada in SoHo, New York City opened with a host of painters, fashion designers and textile artists. Silk-ruffled skirts by Tia Adeloa hung in transparent binders from the ceiling, and luscious paintings by artists like Obi Agwam and Milo Davis contrasted the egg-white walls and cold stone floor.

Through its de-and-reconstruction of place, Strada strives to be a symbol of artistic ingenuity and simplistic timelessness, rejecting the melancholic emptiness that buffets innovation. Strada holds space and survives as a container in which every peek is defined by its audience. Intentionally or not, Strada provides the opportunity for more because it’s essentially an empty canvas that begs the question, “How does one transfer place through space and spirit?”

Pieces by Tia Adeola, Milo Davis, Thomias L. Radin, Augustina Wang, Qualesha Wood and Obi Agwam highlighted temporal imagery and encapsulated timelessness by using nostalgia as a centerpiece for personal growth. Through it all, creatives of all kinds loomed to support.

Strada Gallery is an innovator in contemporary gallery spaces for having been a fresh name before it opened its physical place. Since 2021, Strada has functioned as a traveling gallery that pops up among U.S. cities and states. The Harlem-born founder of Strada Gallery, Paul Hill, developed the space to serve emerging artists.

Strada Gallery finds and provides a physical and foundational exhibition space for overlooked artists. At each event, multiple burgeoning Black and Brown artists feature paintings, photographs, textiles, fashion and curated ensembles under Strada’s roof. By practicing consistency and balancing community orientation, Hill developed a name for himself as a visionary in art space-making. The vision came to life in 2022 when Strada Gallery was awarded the Visionary Small Business grant, a $100,000 grant in partnership between Instagram and the Brooklyn Museum.

By its attempt to break conventional association with form and being, Embodied Spaces prompted a transcendental awareness of presence. Among many messages and themes, the selected artists agreed on object impermanence and highlighted their nuanced relationships with the past, present and future. At the September showing of Embodied Spaces, spirit became the medium through which space and light texture—light’s dispersion across a bending texture—unraveled.

Only days after the opening exhibit in its permanent new space, Strada Gallery disassembled Embodied Spaces and invited curators to organize other art, photography and fashion in its place numerous times. Seeing Embodied Spaces as an ephemeral place, which now exists uniquely in each visitor’s mind and memory, moves the gallery from a mere moment to a timeless monument. For this, the gallery’s intentions to distort space by redefining place and distilling spirit through a normally blanched gallery environment succeeded by elevating the sense of place from a physical space to a metaphysical idea. The idea is rooted in memory formation.

All selected artists’ works were rooted in the ephemeral. In Tia Adeola’s clothes, white light supply spread across pedal-fashioned garments in skirts and pants, which added a new definition to bloomers. Hung still on display and sandwiched between thick plastics, Adeola’s pieces unsettled audience expectations of what a gallery could be by literally upholding apparel that defied conventional presentation. Beyond the presence of Adeola’s pieces, visitors became the subjects of change in front of unwavering paintings, which played with light texture and the impact of time.

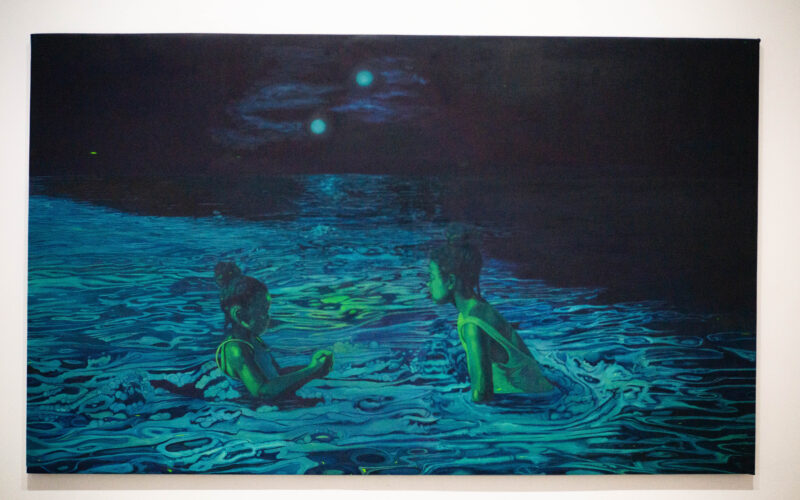

Near the left-most wall, Milo Davis’s oil painting, Birthright, set two lifelike childish figures in a flush of water. They basked under a cold moonlight film. Balance functioned through the rhythmic water, which analogously complimented the emerald-green figures that seemed to be at the threshold of adolescence. Davis’s painting captured adolescence’s ambiance through the figures’ composition.

Both children were composed at play in complex waters that carried light, forming a sense of safety when juxtaposed against their callously dark surroundings. Their position alluded to the safe space that ideal youth occupies among the unforgiving depth and weight that arrives at maturity. By contrasting light and texture so gently, Birthright commanded audiences to feel the gravity and space in which youth rests, like water, like the process of continuous growth.

Movement director, performer and international painter Thomais L. Radin showed a piece inspired by dance and fragmented memory. The sharp and round shapes used along the upper back of the figure created a sense of motion and formlessness that pushed Embodied Spaces‘ intention by showing the body as architecture. The mark-making highlighted distress through dripping paint-driven motion and portrayed the body and moment as moving.

Movement eloquently distanced the audience from this place to the effect that moving away from the piece evoked the fear that it would be gone at a moment’s notice. The way brush strokes breathed light into the gesture complicated whether the piece was making or unmaking itself, which contextualized a “vanishing point” as a matter of when as opposed to where.

Textile art by Qualesha Wood alluded to early-internet aesthetics married with reflective self-portraits. The themes in her work harkened back to Microsoft Paint and the age of internet avatars, which served the idea of consistent self-definition. Wood’s pieces embodied the space of ever-developing Black femininity by having paralleled maturity and personal development with technological advancement and cultural genesis.

Her bold and blatantly wistful 2023 jacquard woven piece, AFK, showcased nostalgia through the hands and heart of a mid-20s Black woman dwelling between longing for the past and appreciating the present. Her work depicted a self-aware and moving mind by juxtaposing imagery of multiple open tabs, alluring glares at the audience, and digital iconography, which invoked cherubim preeminence. Wood’s textiles embodied space that asserted Black feminine grace, futurism and social awareness through its focus on gazes.

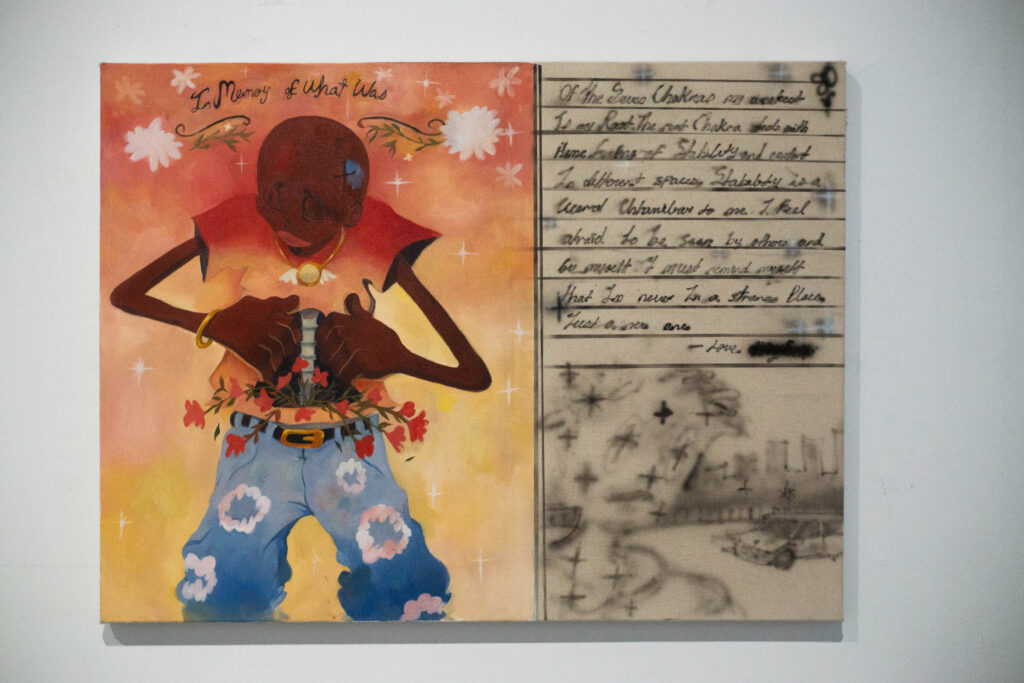

The arguably final piece in the gallery centered on a Black caricature illusory persona bearing its spine with luscious vulnerability. Obi Agwam’s painting, You Can See Me, Flaws And All delivered on spirituality with stark attention to lush gradients and colors nestled in the scheme of a spring sunset. The caricature’s airbrushed writing, “In Memory of What Was,” grounded Embodied Space’s theme of spirit in space and place. The airbrushed passage sharing the canvas of the caricature touched on yearning for home, stability and Agwam’s bout with visibility. You Can See Me, Flaws And All dug into the fear expertly sewn into the skin of those strong enough to unabashedly share themselves with art.

In retrospect, the exhibit used spirit to root the space into an idyllic place raised by the self-awareness that it would soon pass. Embodied Spaces took on conceptualizing memory with Afro-diasporic artists whose works elegantly captured how light, texture, form and community cache moments, which elevated mundanity to memory.