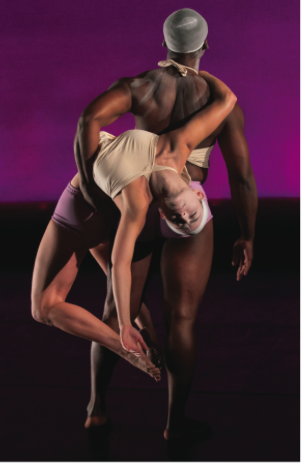

Featured Image: Messenger 9.2 | digital photograph | 2022 / Arnaldo James

1/17/2023 – Speculation: to ask what if and what could be? Unfolding into possibilities that exceed the confines of what is socially prescribed or the limited options made available. I reckon with the power of language, grasping at the contours of words that shape societal structures and dictate the worlds we live in. Discourse configures material life. And yet, I know the depth of emotion and the magnitude of violence cannot be held solely through words. Speculation is a doing, a gesture to what may not be seen but felt or sensed. There is no certainty, just a question of what if and what could be.

Conclusions can be traps, so speculation is a dive into questions rather than answers. Do we trap ourselves because the idea of more possibilities, of other ways of living, brings anxiety amidst a world that declares vehemently that this is it, there are no other ways one can be? I crawl into this question, sit with my own anxieties and ruminate on these thoughts through the work of Ada Patterson and Arnaldo James. Both artists create through speculation, drawing viewers into visual landscapes that embrace opacity and require imagination.

Ada Patterson’s multidisciplinary practice weaves together narratives of Caribbean and queer subjectivity, residues of colonialism, the violence of tourism and desires for intimacy. Born and raised in Barbados, she draws on the natural environments of the region and relationships to water. The sea, rivers and aquatic life forms feature prominently within her work. Patterson’s performance pieces and video work, which often involve costuming, explore Caribbean cultural histories, invoking folkloric figures such as the soucouyant (an old woman by day that at night can transform into a fireball and feeds off the blood of humans and other animals. Her victims wake up with blue-black marks on their bodies where she sucked the blood. If she takes too much blood, her victims may die and become a soucouyant or die and leave their body for the soucouyant to inhabit), jumbie (a spirit or demon, often appearing as a shadowlike figure or inhabiting other life forms such as the echidna (a spiny anteater, a small mammal covered in sharp quills that it uses for protection) and the mangroves.

Patterson employs costumes to provide anonymity to the performer, with viewers fixating on the being brought to life rather than the person underneath. Doing so creates a distance between the artist and her audience, perhaps a level of emotional safety. In Mangrove Village (2019), she embodies a being layered in seaweed and speaks of a life left in the swamp, decomposed by the natural elements. It may be the documentation of a death or an abandonment—sometimes, the two result in a similar end.

In Echidna, I think about the attention that difference brings, and what tactics one uses for protection against unwanted advances. Similarly, Lookalook grapples with societal marginalization, navigating space while embodying difference. In choosing to portray abstracted figures, forms that escape definition, Patterson asks viewers to enter into peculiar or unfamiliar territory. For often, that which we do not understand is approached with scorn, generated through fear. Perhaps offering notes on queer life …

Looking for ‘Looking for Langston engenders the experience of yearning. What kinds of pleasures can one find in the sea, away from peering, judgmental eyes? Citing Isaac Julien’s pivotal film, Looking for ‘Looking for Langston (Sankofa Film and Video Productions, February 1989), Patterson’s piece meditates on the undercurrents of desire, the pressure that fills a body aching for another. To be a voyeur, unable to touch the subject of your longing, for the world you inhabit keeps it out of reach.

Expansive landscapes pull the eye beyond the horizon in Arnaldo James’ new photographic series, In the Interim-Messengers. The figures in James’ photographs embody spiritual and cultural imagery from a range of influences, including Spiritual Baptists, Trinidad Orisha, Moko Jumbie and Carnival Mas tradition practitioners. Did all the Moko Jumbies who walked across the ocean, forging diasporic paths from Africa to the Caribbean, finish the journey? Do some still remain in the water? Standing at what seems to be more than 20-feet tall, the figures command an otherworldly presence.

Each figure is masked, and the anonymity allows them to transcend individuality, a reflection on collectivity. With no explicit indications of gender, they embody masculine and feminine aesthetics much like the orishas—an understanding that gender and sexuality are expressions rather than fixed categories. Both Patterson and James draw on Afro-diasporic spiritual practices, from orishas to obeah and thinking about the relationship between queer subjectivity and spiritual traditions. Is there a space for queerness in these practices, even as it is denounced by Western religion?

Masquerade denies the demand to know who or what lies under the costume. Rather, one must engage on a level that does not require “totality” of knowing, so often a characteristic of spirituality. Blue and white cloth billows in the wind. Palm leaves intricately woven into latticework adorn a figure who emerges from the mud. Silver sequins mask their faces. There is a delicate quality to the elaborate pieces each figure wears.

Through wide-angles, James creates images with immense visual depth. The vastness extends beyond the visual—what else can the mind conceive even if it’s never been seen? The rich landscape of Trinidad and Tobago serves as a meditation on the possibilities that emerge through an intimacy with the natural environment. I consider the images a contemplation on the spiritual vibrations that emanate through Black life, the ways Black people forge space and make meaning. And when this world is not enough, where else can we find refuge? Perhaps it is time to return to the ocean, to find the other Moko Jumbies who did not or chose not to make the entire journey.

Both James’ and Patterson’s work conjure questions of relationality. How do we move in space with one another? How do the intimacies of our lives shape our experiences of the world and conceptions of self? For those to whom the world is cruel, what other lives or new worlds can they speculate?

For more on Gervais Marsh’s practice, you can visit https://www.gervaismarsh.com/