There are those who dedicate all their vision, their potential and their gifts in service to the upliftment of other people and our collective possibility. Ashara Ekundayo has committed her life to service and the affirmation of Black people, including Black women and Black creatives. From Denver to Detroit to San Francisco, the curatorial, photographic and consultation practices of Ekundayo have motivated critical discourse, healing and prosperity for the communities she supports. The model that her process and practice sets is one that proves that pedagogies of healing and communal respect, ancestral awareness and collective growth will continue to offer solutions to the conditions and realities our generation is forced to address and hopefully resolve, so that future generations will be free from the burden of that work.

From 2017-2019, Ekundayo ran her own brick-and-mortar radical Black feminist arts and culture platform and gallery, the Ashara Ekundayo Gallery (AEG) in Oakland, California, which lives on as a nomadic pop-up experience. She has supported iconic recurring exhibitions, including The Black Woman Is God, founded and curated by Karen Seneferu and Melorra Green. She hosts an ongoing live zine series with the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) entitled, Blatant: A Forum on Art, Joy and Rage. She is also a prolific curator. Recent efforts include group exhibitions Collective Arising: The Insistence of Black Bay Area Artists at the Museum of Sonoma County and Salt to Catch Ghosts at /(slash) Gallery in San Francisco.

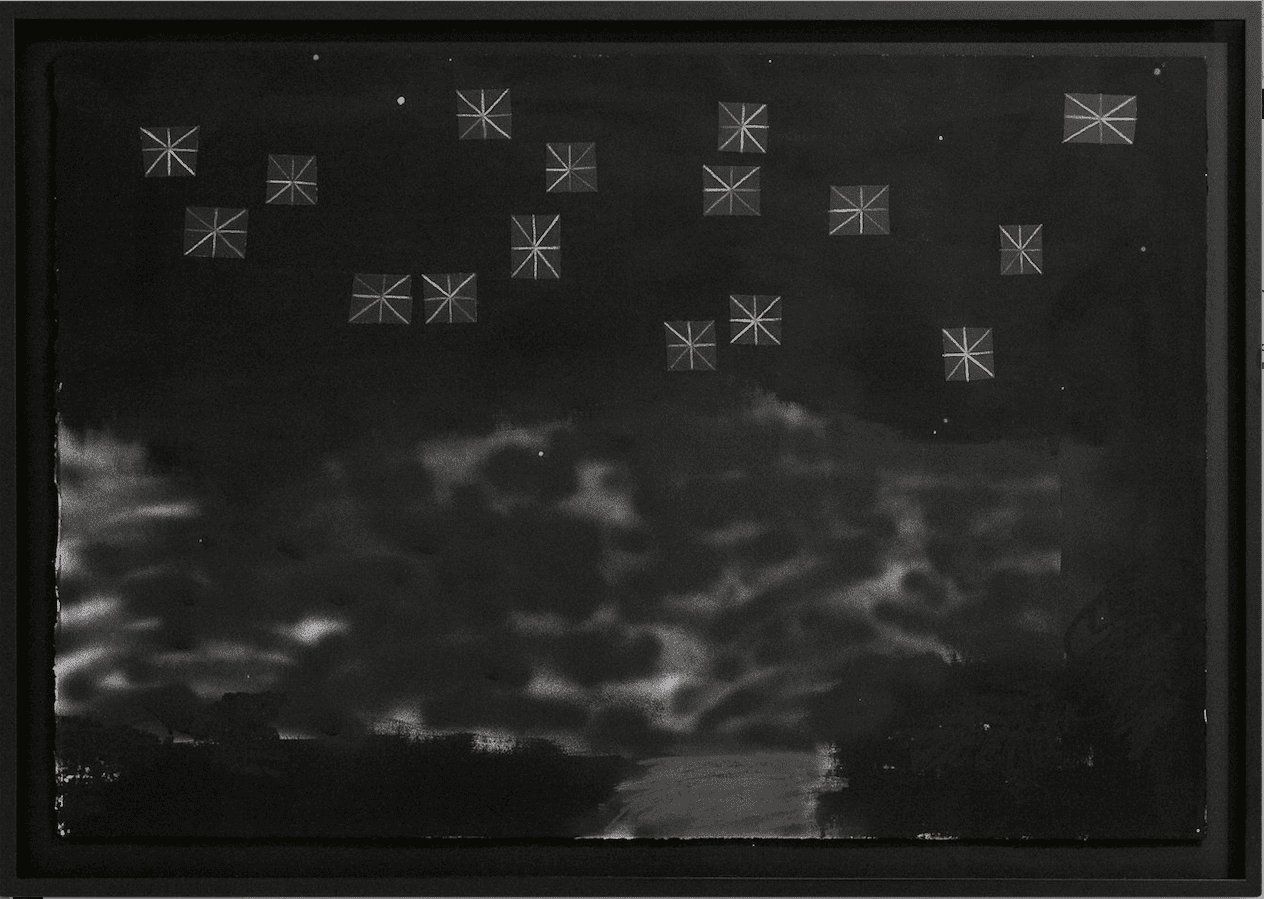

Above- Muzae Sesay, We’re Out With The Stars Again, 2019. Acrylic, oil paint, aerosol, colored pencil, gaff tape, graphite on paper 35 x 49 inches (Framed in museum glass). Courtesy of the artist and Pt.2 Gallery, Oakland.

Surprisingly, no publication has been written yet that fully catalogs the practice, process and pedagogy of Ekundayo’s creative career. Such accolades rarely are given to curators, and those who work behind the scenes to sustain the art practices of other artists do not always get the credit they deserve while they are alive. This profile offers flowers to a genius savant whose extensive history and consistent dedication to Black creativity continue to assert her as an important model and mentor. Her steadfast and powerful reflection offers us a new perspective on our individual potential to bring healing and beauty into the world by affirming and helping others gain whatever support they need to realize their creative goals.

Some may consider it foolish to pour into others with no guarantee that they will pour back into you. The scarcity and competition models we have all been scarred by make it difficult for many of us to imagine a world where reciprocal systems could bring about wealth, health and well-being for us all. Ekundayo’s unflinching commitment helps us better understand that if we hope to see any sustained change, if we hope to activate any sustained transformation in our world, it will be through the formation of infrastructures that align with mutual respect, equity and deep consideration for the world we all inhabit.

Ashara Ekundayo: I chose to live in Oakland, California. When I was ready to leave Denver after living there for 29 years, it was either Brooklyn or somewhere in California. And the question really came down to how fast did I wanna run. At that time, it’s like, “Okay, you’re 40.” Honestly, I was at a depressed state, an emotionally broken state, when I left. I didn’t have it in me to grind in the way in which I would need to grind to live in New York. But the choice to go to Oakland had to do with the fact that I had been going there for some years, and I fell in love with the history and the tradition and the intentional modeling of love that the Black Panther Party shared and gifted to the world.

We use these fancy terms like curator, and they’re tied to the academy, but I’m an arts organizer at the beginning of the day. I’m an organizer and an activist and was raised that way, and my work, my artistic work, my academic work, my community work in Denver for those years was very much as an arts organizer and cultural worker. So, Oakland felt like a space that I could land and learn some more and explore.

There were some spaces in Denver that I could not penetrate. You cannot penetrate the gallery world there, the white supremacy, the anti-Blackness. The blatant racism in Denver inside of the art sector at that time was very thick. I wasn’t coming out of the academy with a BFA and an MFA. I wasn’t connected to any Black galleries. I didn’t have a model. I didn’t have a mentor around, but that was what I wanted.

That led to me saying, “where’s the place where there are some models?” And at that time, Oakland had Black galleries and artists who were doing really innovative work around economies and starting to think about new ways of creating spaces and residencies, so I was able to go into a place and bring the understanding that I have and the experiences that I had of running the Pan-African Art Society in Denver for 15 years and the Denver PanAfrican Arts Festival and youth organizing to Oakland. I had also been the Colorado fellow around food justice with Van Jones, who also founded an organization called Green For All.

There were several Green For All’s all over the U.S. who were working in food justice, urban agriculture, clean economies, clean energy, and this was right as the idea, and the funding for green jobs came through the Federal pipeline. That gave me the opportunity to travel and sit with other like-minded folks, mostly folks of color who were creatives in their communities, but who were working around climate justice. My acumen around incorporating cultural practice and prayer practice into that work was kind of the sweet spot for me.

And so, when I first moved to Oakland, I was still working in Denver with the U.S. Department of State and a nonprofit organization there, and I was the lead administrator for an international food justice fellowship between Uganda, Kenya and Denver. And my co-collaborator and co-director was Erika Allen, who is the co-founder of Growing Power in Chicago, which is now the Urban Growers Collective. Her father, Will Allen, was the first farmer to get a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant award.

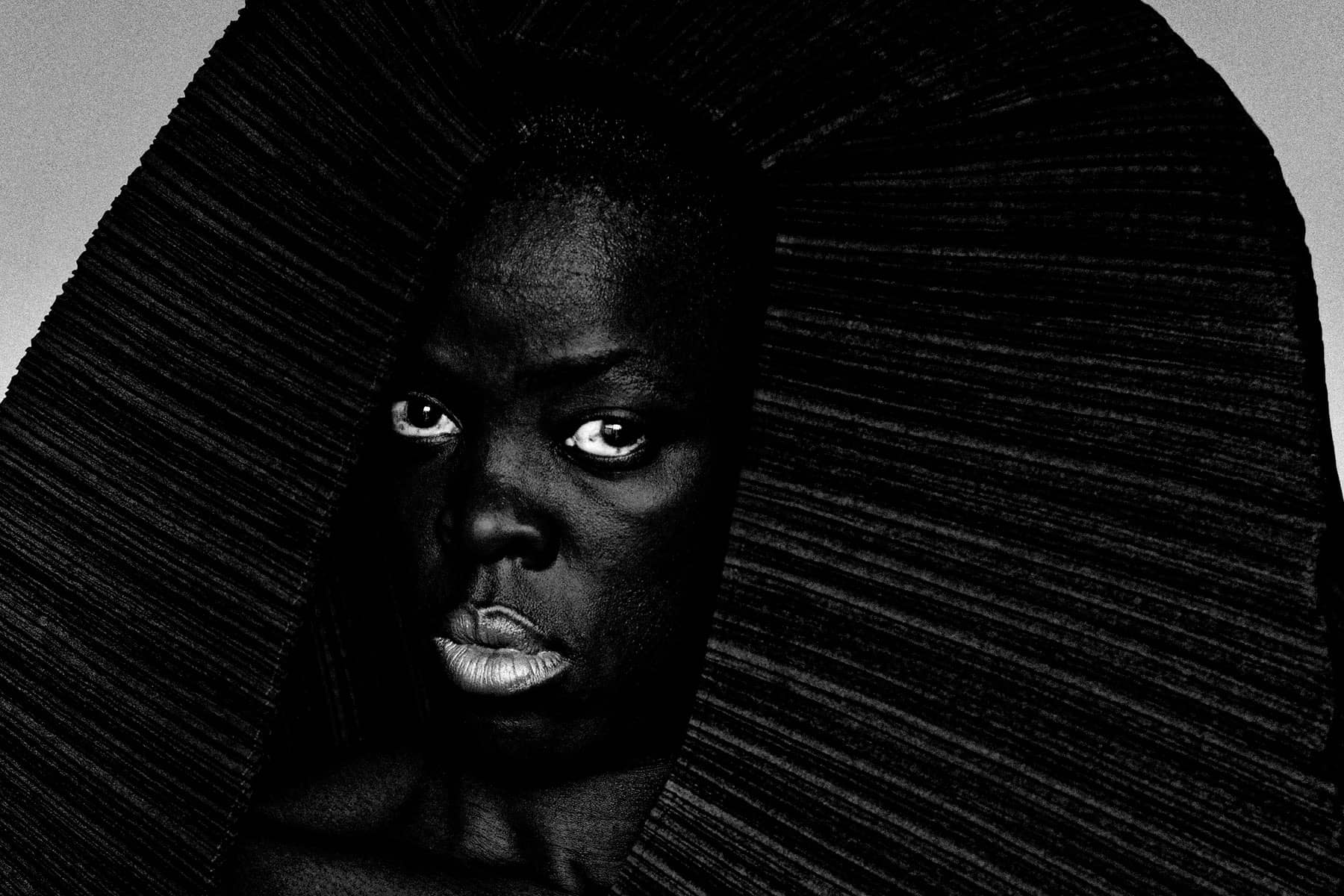

Above: Adrian Octavius Walker, STILL Pushing Through, 2022. Archival pigment print, 10 x 8 feet. Courtesy the artist and Pt.2 Gallery, Oakland.

Angela N Carroll: Let’s talk about some of the major projects you have created while in Oakland. I’m inspired by the way you create generative platforms that support individual artists and broader art ecosystems. Artist As First Responder is a great example.

AE: Well, I see Artist as First Responder as my curatorial practice, and when I look at what are the ways in which I work, as you said, a creation of space and platform, what does it look like? It looks like exhibitions, and it looks like a public forum, and it looks like printing and publishing, which is something that I’m very interested in and new to. It looks like site-responsive or specific ceremony, and it looks like artist residencies. Those six prongs inside of what is now this organization are a way for me to, I think, experiment with funding around it and allow people to be mentor and to be student simultaneously. I’m just not interested in platforms that aren’t about abundance and us being generous with each other.

So, in terms of what it looks like to be in a space of generation and regeneration, my permaculture training or permaculture mind says there’s something really juicy at that edge between the two systems that may seem disparate, and that’s the place for me of creation. That’s the place of experimentation, and if other folks get to benefit from that, that’s cool too.

AC: You occupy so many spaces and don’t really fit into one category or box. How does that support your art practice?

AE: I’m not squarely an arts writer or art critic, and I’m not squarely a practicing visual artist. I am a curator, and that’s my art practice, and so it’s as diverse as whatever my mind wants to turn its attention to. That has only happened because there are people who want to collaborate; it’s a collaborative practice. When I was at the college, I had really generous, mostly Black, women academics who just by saying, “Yeah, you can do it!” gave me permission in the same way in which my mother gave me permission to be a dark skin, Black woman who could do anything. That was the gift that she gave me every day, because everything outside of my home told me that I could not.

AC: Can you share some thoughts about the importance of collaboration for your curatorial art practice specific to the residencies that you develop?

AE: I think one of the things that’s really wonderful right now are artists and curators and other creative folks who don’t identify with any of those labels, creating intentional space for us to take time to be in residency. So, this Artist As First Responder arm around artist residencies has been really powerful. We have a partnership with Black [Space] Residency, which I co-founded with Erica Deeman, who’s an interdisciplinary visual artist living between San Francisco and Seattle now. It’s a separate entity, but it really allows for both of us to try to think around what is the kind of care space that we would like to have, and to create a space where the person in residence doesn’t have to pay to be there.

There are some supplies and resources for them in a building where there are other people who will help them, and equipment. We give them some money, too. The residency was initially funded by other Black artists. We know that we are not all starving artists, so we are stepping deeper into that thinking. It was a two-year experiment and partnership between Artist As First Responder and Black [Space] Residency.

Artist As First Responder also has climate justice, social justice artists and residents, which I would say it goes back to my beginnings. We’re the artists who are living at that intersection all the time, so there will always be a part of our narrative that is about that. We are making sure that we are caring for and paying attention to the beings on the Earth.

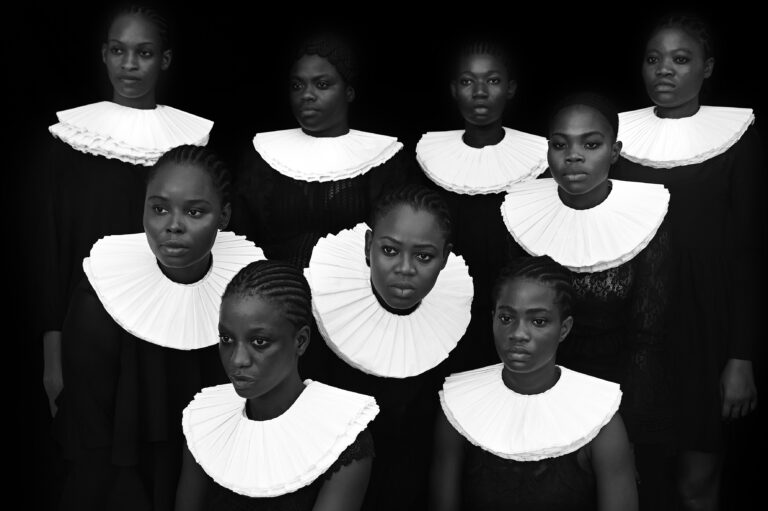

Above: Muzae Sesay, Peacemaker, 2021. Oil on unstretched canvas 2 x 8 feet (each, 8 total), Courtesy Adrian Mendoza Photography.

AC: Do you see any barriers to connecting Black Bay Area artists with Black artists in L.A.?

AE: In the last decade, many Black artists have left the Bay Area mainly because the housing market in the Bay Area is outrageous. That’s because artists are not readily supported by the city of Oakland. The city of San Francisco more so, but still, we’re talking about a rent percent that matches New York City. Oakland is now as expensive as San Francisco, and costs did not go down during the COVID-19 pandemic, costs went up. More and more people were pushed out onto the street, and so many artists, as many people did, started re-evaluating what’s important. What does quality of life mean to me? The Bay Area is experiencing a creative drain to Los Angeles right now.

If you have the time and money to travel down the highway for five hours, it’s a good thing to do, because it’s a different vibe. There are so many more indie spaces in Los Angeles, there’s so much vibrancy in the independent art scene, and there’s so many more museums. I think there’s some space for artists having some generosity with their time there, because they have spaces for it. So, I think that if the Bay Area is going to survive, if the Black artists are going to survive, that it would be good for us to continue to hold those relationships and try to build them out.

AC: What are your hopes for the future of Black art in the Bay Area?

AE: In the Bay Area, I hope that creative folk, that cultural workers, arts organizers, activists, and curators find ourselves in love with each other again. We actually need each other, and we would be stronger if we could allow ourselves to share with each other. We have to stay present and understand that there is enough and that we can give from the overflow and not compete for what’s at the bottom of the barrel.