Basil Kincaid (they/them/theirs), born in 1986 in St. Louis, Missouri, describes themself as a “post-disciplinary artist who explores the fixity of conditioned and self-imposed constructs.” Finding a balance between moving beyond these conditions and preconceived notions, and retaining a fluid yet defined connection to heritage and ancestry is central to Kincaid’s practice.

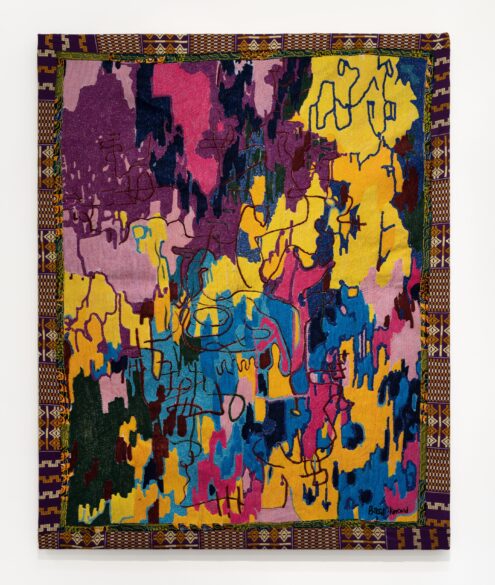

Kincaid moves and thrives for a freedom of spirit and mind, exploring beyond boundaries. Their understanding and love for their ancestral inheritance is a source of power that creates a sense of being limitless rather than confining. The use of fabric—whether family clothing, found scraps or handwoven Kente cloth and various other traditional or contemporary African fabrics—allows Kincaid to stitch together narratives that reference personal stories and merge them with histories that connect people beyond an intimate space or direct personal references. The created spaces and landscapes sprawl across quilts that are not limited to singular meanings but rather a multitude of signifiers that merge cultural contexts and find them signified regardless of place and identity.

Weaving a new cultural fabric or a multitude thereof—that is based on freedom, imagination and liberation of spirit—creates a contemporary dialogue that does not stay on gallery and museum walls. Cultural fabric is everyday life. It defines our cores and interactions and guides decisions. Wrapping ourselves in quilts of new ideas and freedom moves us into a realm of fluidity. Kincaid guides us along the way.

Quilting has been a tradition on both sides of the artist’s family for multiple generations, and their cherished childhood memories include their grandmother quilting or working on needlepoint, which led to many moments of observation, dialogue and learning, and eventually a natural progression into the quilt as an artistic medium.

Above: Basil Kincaid in his studio in Ghana.

The quilts they create are in many ways wearable and have a close connection to the wearer or anyone who touches them—from the person who originally made the fabric to those using and wearing the fabric, Kincaid themself as the artist creating the artwork, and everyone who spiritually or intellectually inspired them.

Whoever gets to live with one of Kincaid’s works may do so in many capacities as their quilts can have a spiritual impact and can offer transformative experiences. What imagery is depicted? What fabric was used? Whose spirit has touched the work? What does the practice of quilting mean, and what meaning does this tradition introduce into someone’s home? How does owning a quilt and understanding the historical and cultural significance challenge ideas or even preconceived notions?

Kincaid gravitates towards fabrics that have been lived in, and the fabrics always have a strong connection to place. When working at their Ghana studio rather than the St. Louis studio, the artist uses more local fabrics sourced at the market. The fabrics tell an abundance of stories on their own, as meaning is woven in each thread and color or motif choice. When working in the U.S., Kincaid gravitates more towards secondhand fabrics or fabrics gifted to them by relatives and friends, adding inherent stories and an intangible essence of past owners to the artworks.

Colors, textures and fabric weight are all factors the artist considers when placing fabrics together, even disregarding certain quilting traditions as their artistic expression doesn’t require conformity or strict aesthetic definitions. Rather, mistakes harness power and authenticity, with every mistake being a new style and not a mistake after all.

Quilting, fabric and associated traditions of weaving, storytelling and life—all of these need to be considered with conscious effort. The works demand thought and care and respect, not just for the artist personally, but for all this stands for: African traditions and cultures from various parts of the continent, continuity in the Americas, syncretized cultural forms and the historical realities that are at the root of the conditions and traditions. One cannot own a quilt without also living with history, acknowledging history, interrogation and questioning, and considering the future. The post-disciplinary artistic space ultimately requires everyone who engages with the art also to push to the next chapter in facing the past.

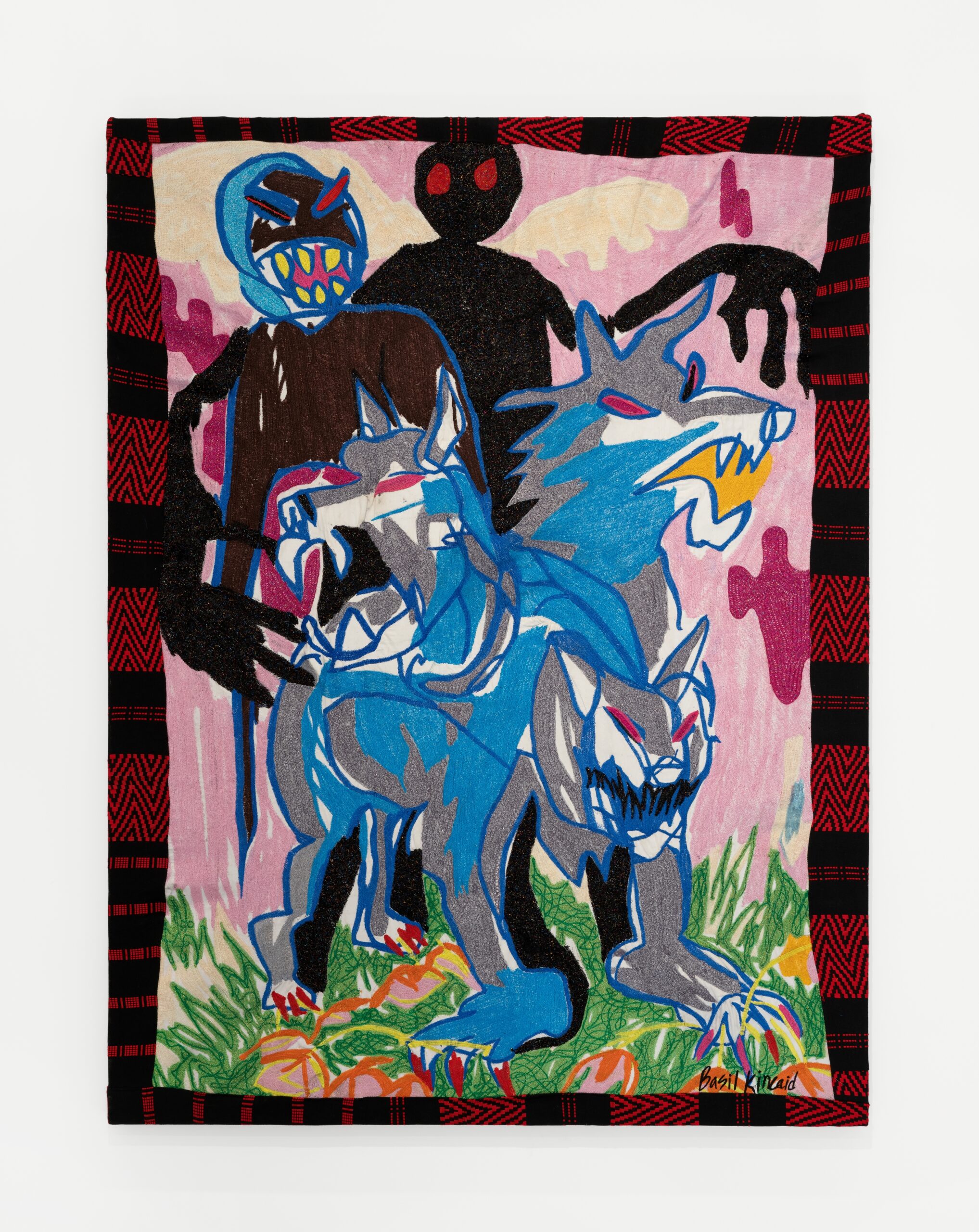

Above: Work by Basil Kincaid.

Reality is as much a part of Kincaid’s work as mythology. The two realms are as closely knit together as ancestors and descendants yet to be born. Kincaid forged an even closer connection to ancestry by establishing a second studio in Ghana. Retaining a studio practice in Ghana and being able to create there proved to be an integral step toward growing into their own practice, maturing as an artist and sharing a multitude of narratives in additional tongues that now encompass new experiences. It signifies a connection to ancestry and heritage that infuses existing narratives with not just strength and power but also mythological layers.

Ghana allows Kincaid to manifest their imagination in a way not perceived as possible before by the artist. Significantly, the close collaborations with Ghanaian artisans and incorporating embroidery into their practice encouraged new ways of seeing and expressing. The embroidery presents a continuity to a practice based in fibers, and even the embroidery works include quilting elements in the Kente cloth trimmings. The continuity that is so obviously present is truly poetic in the way it elaborates the past and elevates the present. It also hints at what is yet to come. To Kincaid, Ghana is defined by the sun and represents space, self-care, expansion and community.

Kincaid’s visual poetry creates speaks of all of this in the choices of colors, the abstractions that grasp emotions that the figurative cannot contain, and the text and figurative elements that represent the artist’s interior world. The figures that have been part of Kincaid’s practice for the past 20 years can be as literal as family, as conceptual as emotional and spiritual extensions, or as anthropomorphic representations.

Kincaid’s connection to heritage also is connected closely to land and the ontological signifiers contained in landscape. They often equate their artistic practice to farming—process plays an integral role. A process that cultivates an environment with fertile ground to blossom. The artist and the art grow in a space that allows for spiritual liberation and derives meaning from the process of engaging with a given landscape and its cultural and epistemological markers.

Kincaid’s works pass on knowledge, traditions and a spirit of freedom that transcends the boundaries of art. The narratives cannot be contained by definitions of artistic disciplines, genres, mediums, prescribed identities or art market trends. The artist creates for themselves and for everyone willing to connect and find meaning.