This week in African art and culture, the 1-54 Contemporary African art fair, Africa’s biggest art fair, kicks off in London. Also in London, a group exhibition featuring emerging artists from Democratic Republic of Congo opens. Sadly, we report news of the passing of one of Africa’s renowned abstract painters. And on the literary scene, another African author has his work going to screen, and a Ugandan writer has won the PEN International Writer of Courage 2021 award.

1-54 Contemporary Art Fair Kicks Off at Somerset House, London

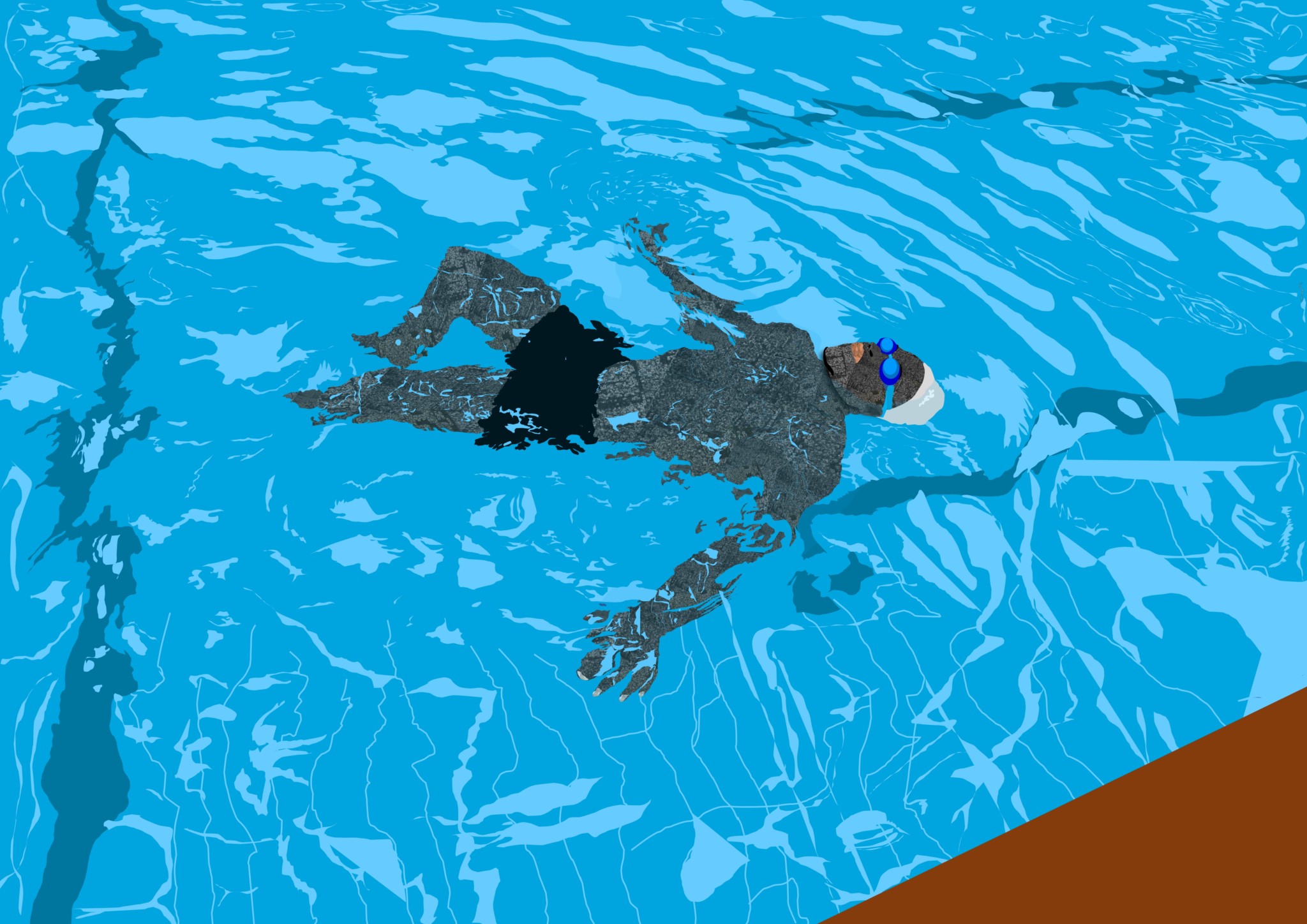

Above: Osinachi | Man in a Pool III | 2021 | Courtesy of the artist and Daria Borisova (participating in The Virtual Salon at 1-54)

This week, 1-54 Contemporary African art fair kicks off its ninth and largest edition yet online, along with a physical event at the Somerset House, London. The fair commenced on Oct. 14, with works from 48 leading international galleries representing 23 countries across Europe, Africa and North America including Angola, Belgium, Brazil, Ivory Coast, Egypt, France, Germany, Ghana, Italy, Kenya, Morocco, Netherlands, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Switzerland, Uganda, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The fair is accompanied by 1-54 Forum, an extensive program of artist talks, panels, screenings, performances and readings that will be curated by Dr. Omar Kholeif, director of collections and senior curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, also taking place both online and at Somerset House. Entitled Continental Drift, 1-54 Forum brings together artists and audiences; mediators and narrators, to collectively delve into themes of legacy, philanthropy and digitality. Exploring this interstitial moment in history, 1-54 Forum explores the concept of the drift as a moment for gradual reflection.

Additionally, as part of the program of 1-54 Special Projects, the fair once again will be partnering with Christie’s to present an exhibition at the Duke Street space, curated by art historian and art critic Christine Eyene.

1-54 Contemporary Art Fair always has been one of the major African art fairs on that has traveled to different cities—such as Marrakech, Morrocco, New York, Paris and London. However, due to the challenges of COVID-19, the fair came to a slow halt; however, with this edition, momentum seems to be picking up again in London. The fair definitely is going to restore the excitement that has been lacking since the lockdown.

The physical fair will come to a close on Oct. 17, 2021.

Breaking the Mould: New Signatures from DRC Curated by Christine Eyene in London

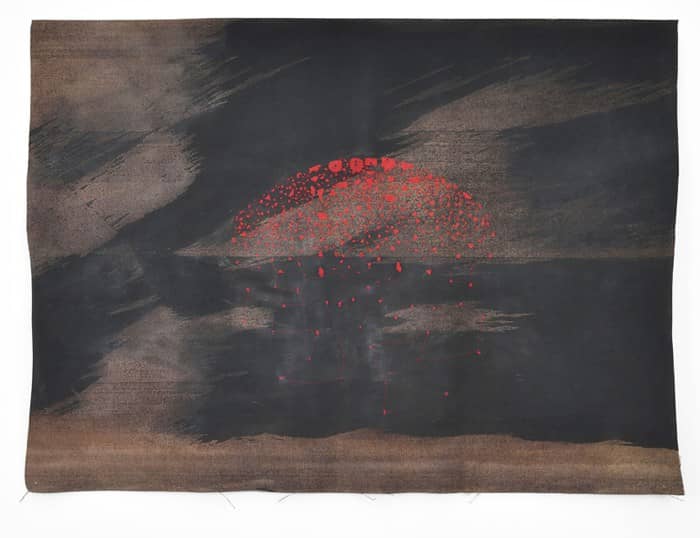

Showing in London is a group exhibition titled, Breaking the Mould: New Signatures from DRC, featuring the work of 12 emerging artists from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), predominantly former students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa, who are breaking the boundaries of academic training and developing new forms of visual explorations.

The artists are Arlette Bashizi, Beau Disundi, Ghislain Ditshekedi, Godelive Kasangati, Anastasie Langu, Jamil Lusala, Catheris Mondombo, Arsène Mpiana, Stone Mutshikene, Chris Shongo, Ange Swana and Joycenath Tshamala.

For this exhibition, which opened Oct. 14, curator Christine Eyene selected over 15 artworks and series comprising painting, photography, mixed-media and installation pieces that reflect the new ideas, aesthetics and discourses emerging from the heart of Africa.

Breaking the Mould: New Signatures from the Democratic Republic of Congo is the artists’ first gallery exhibition in the U.K. It also seeks to place the second largest African country, whose sculptural traditions have had a significant impact on the development of Western and global modernism, at the center of the continent’s creativity.

Alongside the exhibition is planned a public program that will launch during the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair and a catalogue published by Beam Editions with a foreword by Barby Asante and essays by the curator and Lubumbashi, DRC-based art writer and cultural operator Patrick Mudekereza.

This exhibition marks the reopening of the newly redeveloped 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning and is funded by Yetu – Property Investment Club and Arts Council England. The exhibition will be on view from Oct. 14 until Dec. 11, 2021.

Ghanaian Artist and Curator Atta Kwami Passes Away at 65

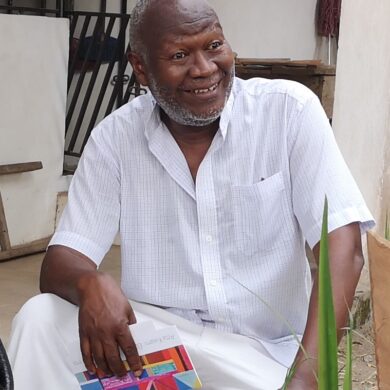

Above: The late Atta Kwami

Atta Kwami, a Ghanaian painter whose abstractions are known for establishing a continuum between Africa’s past and present, has died at 65.

Kwami’s paintings often resemble colorful arrays of geometric forms that are organized in ways that recall grids. But unlike the neat arrangements seen in works by Piet Mondrian and Agnes Martin, Kwami’s compositions are freer and livelier, and often are filled with shapes of uneven sizes, rows of varying widths, and dramatic contrasts between hues. In that way, they are closer to the abstractions of Stanley Whitney, whose work, like Kwami’s, often melds Western modernism with styles associated with jazz and crafts.

Born in 1956 in Accra, Kwami was based in Kumasi, Ghana, and Loughborough, England. In his art, he often alluded to the cross-pollination of European and African aesthetics that he witnessed throughout his career. Among his Ghanaian sources were Ewe kente cloth and the sounds of the folk musician Koo Nimo.

Periodically, Kwami also worked as a curator and an art historian. In 2013, he published the book, Kumasi Realism 1951–2007: An African Modernism, which explored the growth of an art scene in the city he long called home. The book postulated a style that Kwami termed “Kumasi Realism,” or a Ghanaian kind of painting that emphasized multiplicity, and considered the role that the city’s art spaces played in fostering a local kind of modernism.

He won the 2021 Maria Lassnig Prize, a $57,000 art award that comes with an exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries, and his sculptures can be seen at the Folkestone Triennial in the U.K. In the forthcoming Phaidon book, African Artists From 1882 to Now, Kwami’s work is included alongside that of more well-known artists like Meschac Gaba, Wangechi Mutu and Yinka Shonibare.

When Kwami was announced the winner of the 2021 Maria Lassnig Prize last year, Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, called him “an artist with decades of pioneering work.”

Kwami often talked about the abstraction of his work “My work is described conventionally as ‘abstract,’” he wrote in 2011. “Given that there is a very precise, knowable set of resources at the back of it, I would describe it as schematic: like a map, or rather a reaction to or interpretation of a map. It is about ownership, a way to finding myself, where I am.”

Kwami produced work that can be found in the collections of both the national museums of Ghana and Kenya; the V&A and the British Museum in London; and the Met and the Brooklyn Museum in New York, as well as the National Museum of African Art in Washington. He was working on an architectural installation to be shown at the Serpentine galleries at the time of his death.

Sulaiman Addonia’s Silence is My Mother Tongue Goes to Screen

Silence is My Mother Tongue, by Ethiopian writer Sulaiman Addonia, has been adopted for screen. The Belgian filmmaker Laurent Van Lancker and Addonia won a grant to write a film script for the book.

Addonia shared the news on social media, stating that the decision was made unanimously by some prominent Belgian cinema professionals.

Silence is My Mother Tongue was published by Indigo Press in 2018. It tells the story of Saba, a young free-spirited Eritrean woman living in a refugee camp. It will be exciting to see how the interpretation of the work will turn out on screen.

Addonia joins a growing list of African writers who have had their work transition from novel to film.

Kakwenza Rukirabashaija Is PEN’s 2021 International Writer of Courage

Above: Ugandan novelist, Kakwenza Rukirabashaija

Kakwenza Rukirabashaija has been selected by Tsitsi Dangarembga as the PEN International Writer of Courage 2021 award. The news was unveiled at a ceremony held at the British Library, London, U.K. on Monday, Oct. 11, 2021.

The PEN Pinter Prize is awarded annually to a writer from Britain, the Republic of Ireland or the Commonwealth who, in the words of Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize winning speech, casts an “unflinching, unswerving” gaze upon the world, and shows a “fierce intellectual determination… to define the real truth of our lives and our societies.” Other winners since 2009 include Linton Kwesi Johnson, Lemn Sissay, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Sir Salman Rushdie and Hanif Kureishi.

The judges for this year’s cycle were The Guardian’s associate editor for culture and English PEN trustee Claire Armitstead; literary critic and editor-at-large for Canongate Ellah P. Wakatama, and poet Andrew McMillan.

On June 8, Zimbabwean novelist, playwright, filmmaker and activist Tsitsi Dangarembga was announced as the winner of the PEN Pinter Prize 2021. The prize was to be shared with an International Writer of Courage: a writer who is active in defense of freedom of expression, often at great risk to their own safety and liberty. The co-winner was to be selected by Dangarembga from a shortlist of international cases supported by English PEN.

The selected winner of the International Writer of Courage—revealed by Tsitsi Dangarembga as she delivered a keynote address at a ceremony hosted by British Library and English PEN—is Ugandan novelist Kakwenza Rukirabashaija. He is the author of The Greedy Barbarian, a novel which explores themes of high-level corruption in a fictional country, and Banana Republic: Where Writing is Treasonous, an account of the torture he was subjected to while in detention in 2020.

Dangarembga paid tribute to Rukirabashaija, saying: “My career has taught me that the work of a writer is doing and that when circumstances allow, this doing is, in fact, writing. On the other hand, when circumstances do not allow for the writing process, a writer continues the expression that is no longer possible in literature, or that has become inadequate through literature with other actions. I have come to see that the work of writing is not to be seen to be doing but, in fact, to do and to keep on doing, regardless of circumstances. Only sometimes, if a writer is very fortunate, is that doing seen.”

The author said, “I would like to congratulate Tsitsi Dangarembga for the deserved PEN Pinter Prize and thank her wholeheartedly for having chosen to share with me this prestigious prize. If it weren’t for PEN, I would still be somewhere in prison—perhaps forgotten. When I was hanging on chains in the dungeons, I swore to my tormentors that I would never write again if they gave me a chance to live—as if they were some deities or God. Truth is, I survived death. I appreciate PEN for advocating for my freedom of expression and the different centers all over the world that sent in lovely messages of courage. I received the messages with smiles even though I was in horrendous pain.”

Compiled by Roli O’tsemaye