Jaleel Campbell, a Syracuse, New York-based creative, illustrator, dollmaker, videographer, musician and pop-cultural guru unlocks a distinct style to render cultural moments of Black life. Campbell’s experience, obtaining a Bachelor of Fine Arts in visual communications from Cazenovia College, a Master of Fine Arts in media arts and culture from SUNY Purchase College, and an Adobe Creative Community Fund Residency, fuels his community-oriented practice. He employs a language of visuality that articulates Black memory throughout time.

As a strong believer in Syracuse art, he cultivates relationships with the Community Folk Art Center, Black creatives, and fosters an artprenureal spirit. Even in his apartment space, he curates a museum full of his artwork, décor, and testaments to the Black experience with ephemera.

Chenoa Baker: Which artists inspire your work?

Jaleel Campbell: Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, Derrick Adams, and Synthia Saint James inspire my work. St. James’ work is so simple but so Black. The images depict our culture in such a familiar way. You have no choice but to love it! I’ve been a fan since I was a child. Each artist’s work—unique in style and composition—is what I aim to include in my work.

CB: What is your artist story, was it a clear path or evolving over time?

JC: Yeah, it is still evolving over time. I’ve always been somebody that loved creating in whatever capacity that was meant for me at the time. In high school, I took a lot of art classes, but it was for fun. I wish I would’ve buckled down and that I knew what it meant to go to school for art and what it took. It wasn’t until I was heading off to college that I began to take creating seriously.

CB: I am drawn to your art practice because it knows no medium. Can you talk about why you choose versatility in your practice?

JC: I do illustration work, create cloth dolls, and make video work. I sing as well, and I am often collaborating with other people to make my visions come to life. Any chance I get to engage the community through my work, I’ll take it because I love to collaborate.

My illustration style and all the things that I cover deal with the idea of memory. I am interested in going through glimpses of Black life, whether that was my first series, Ghetto Art Deco: Reimagining the Harlem Renaissance that was geared towards the Harlem Renaissance or Feel That Funk that was based on the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s. Now, I am beginning to reflect on the Antebellum South. I feel like I am traveling through time and history in a modern way. I am actively choosing to rewrite the narrative of Black people from those different times.

CB: How do you tap into that memory? Would you say that you research through spending time with people and learning from their interactions?

JC: Yes, I feel like a low-key anthropologist because I study people so much. I talk with others and pull from whatever they are willing to share with me. I get to these moments of having a thought, and I follow that thought until I cannot follow it anymore. I was extremely sensitive to 70s aesthetics, and I am seeing it everywhere right now, and I wanted to position myself in conversation with this happening all around me. Same thing with the antebellum vibes, after seeing it and feeling it for a year or two now, it is a necessary shift that I need to make in my work. I move off of feeling.

CB: Your graphic design work is known for patterned geometry. Why do you pick geometric form to illustrate the Black body in portraiture?

JC: That gradually developed over time. I began to realize that the more I added different types of angles and shapes, the more realistic they began to look. I’d like to think that they play with the mind, in a sense, because they are extremely flat but at the same time, they’re extremely dimensional. It keeps you busy while looking at each image.

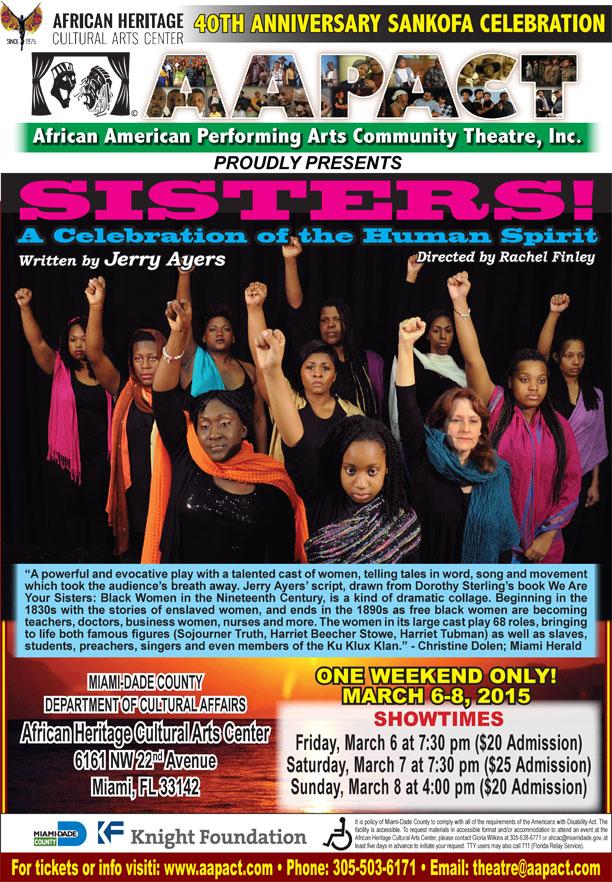

CB: Since it is the anniversary of Feel That Funk, can you describe the process and how you conceptualized your video project?

JC: Three years ago, I was working on Feel That Funk, in which I turned my 70s-inspired illustrations into real life. I wanted to see real people recreate the images that I worked so hard on. That’s where that project was birthed out of. We wanted to showcase Black joy that was very reminiscent of Soul Train and show us having fun, looking fly and doing our thing. When we released that video, we did not know that we had a true gem on our hands.

For the first one to have travelled the way it did, and the second to have me rapping on the song with a whole production team (over 70 people showed up to be a part of this production the day of), I was astounded by the support and love—especially from the Community Folk Art Center to allow us to use the space not knowing exactly what we were going to do but trusting us. I cannot wait until we are able to get back to creating with the community. I want to keep growing to fulfill the Feel That Funk project to see what other things that we can come up with and how people respond to it.

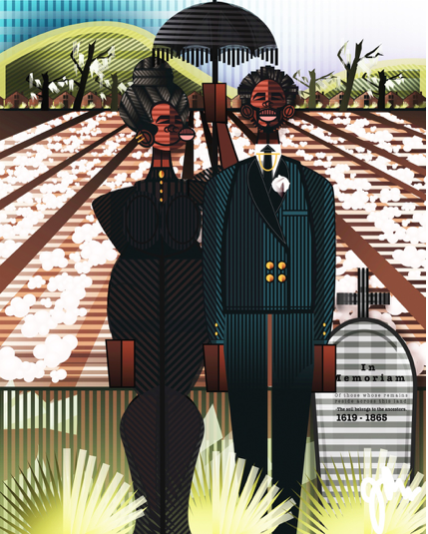

CB: Can you talk about how you translated what Juneteenth and returning to the South means to you in your illustration, Homecoming?

JC: Going down South is a personal experience for me because that is where my father’s family is from; my mother’s family, too. My father’s family knows a lot about our family history. I heard these stories about my ancestors when I was down there for my grandfather’s funeral last year. This struck a chord with me. There is something so beautiful about down South—the air is different, the people seem so magical, and I feel that about myself, but since I do not live down there, my senses are not as sensitive. But the longer I was down there, I was feeling different. That is why I love the South.

That illustration came to me three days before Juneteenth, and I had taken a break from illustrating. For it to hit me the way that it did, I know that it was God. It tells the story of the Black experience. The two figures remind me of descendants of slaves that were heading back down South to visit the land where their family was unable to see freedom. They went to go pay respects to them. It is a humbling experience because they were going to acknowledge those who were unable to see freedom but were also showing how much things progressed and have lifted in the family’s name since slavery. To me, that is what Juneteenth is all about—people that you love. I get so excited when I am building and creating with other Black people. Coming up with these traditions for us to be able to be ourselves freely is very important to me.

CB: Can you describe the impetus for creating your doll project? Are they dolls to be played with or décor?

JC: I grew up loving dolls. I played with dolls, but my father did not like that. Sometimes I used to have to go and hide to play with my sisters’ dolls. Once I got older, I tried to do everything in my power to forget about this. However, it was not until grad school that I had time to reflect and realize that there is so much power in me opening up and telling people how much those dolls meant to me. I began to write and tell my story. From there, I attempted to make my own dolls that were reminiscent of me. Over time, they got better and better. Imagine that—I was as a child, playing with dolls, which was so shunned, but there is so much power in these dolls because they are little versions of me.

Originally, when I was creating them, I did not even have children in mind. I thought that they would be décor pieces—just something to have in the house. But when I saw the reaction to these dolls from little kids, I realized that they love these dolls. I created the dolls in a gender-neutral way, but when people play with them or hold them in their hands, they would come up with the gender for the dolls on the spot. From that, I decided to keep gender open-ended, because some people want to make the gender of their doll. Eventually, I want to have two versions of my dolls: cloth dolls that are meant for décor for collectors and a more accessible version where little kids can play with them without having to worry if they will break them.

CB: In publications and on your website, you are noted as a “community artist.” Can you talk about what that role means to you?

JC: I consider myself somebody that comes up with a lot of inventive programming to engage with the community and bring them into spaces that puts them in conversation with my work and with these institutions. It is so important to have these bridges. For example, I try to direct people to be a part of non-profits like the Community Folk Art Center. This is a Black space for us to use, and I am trying to show people who may not necessarily be around the art community in Syracuse on a daily basis that they can still engage with the space, there is so much to do there, and it is so much fun.

CB: How do you feel about Syracuse and envision it as an artist?

JC: I love Syracuse because I was born and raised there. There is so much untapped potential, and I believe that we are going through a renaissance creatively. I am trying to be at the forefront of that. I am trying to make some noise that we can take this to the next level, whatever that might mean. I don’t want to leave anything on the table that is untouched. I want to cover all bases and dominate the city with my artwork.

View more of Jaleel Campbell’s artwork on his website, JaleelCampbell.com and follow him at @jaleelj.blige