I read all these books on art collecting, and they were wonderful books, but they were written by white males or females, talking about white collectors who collected white art. So I was like, where is the book about the Black collectors who are collecting the work of Black artists?- Charles Moore

In Charles Moore’s latest book, The Black Market: A Guide to Art Collecting, Moore deconstructs the mystique of the Black art market in a condensed manner that introduces the basics of the art world. Unlike other art introduction books, he tailors his writing towards the Black collecting experience, highlighting prominent Black artists, Black art professionals and museums located in areas with a large Black population.

In search for information on Black collectors collecting Black art, Moore developed The Black Market to give a glimpse into the ever-evolving art world. Moore defines important factors in the art industry and the roles they play in the development of an artist’s career.With chapters such as “Museums,” “Galleries,” “Art Fairs,” “Art School Residencies,” and “Art Collection Management,” The Black Market gives new art enthusiasts the confidence to enter the art world independently.. Moore designed this book with the objective of being applicable for both the inexperienced and experts of the art world.

Charles Moore introduces art collecting with a brief history of significant Black artists who have influenced 21st century art, accessibility and the way we view art. In chapter 2, “One Black Artist Born Every Decade,” Moore uniquely introduces, by decade, one Black artist of prominence starting from 1900 and concluding in 1990. Highlighting “that there have been artists for a century making art in America, and there is,” indeed, “an African American art history.”

Here, Moore briefly describes the evolution of each artist, the context behind their practice, and a well-known work of art produced by the artist. He highlights artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Kerry James Marshall, Renee Cox, Derrick Adams, Mario Moore and Tschabala Self. This section is important, especially for individuals new to art. The chapter provides a list of important Black artists to familiarize yourself with and allows you to learn about the details and trajectories of their careers. While there are no pictures included in this book, Moore names specific artworks in this chapter that one can look up while reading for a complete comprehension of the artist and their work.

Moore dedicates an entire chapter to different art books that he suggests would be beneficial to read. Listed throughout the book are valuable resources for the reader, including recommended reading and photobooks for beginners to understand art in addition to a glossary of art terms at the end of the book. Ways of Seeing, by John Berger is listed, as well as Carrie Mae Weems’ Three Decades of Photography and Nate Lewis’s Latent Tapestries.

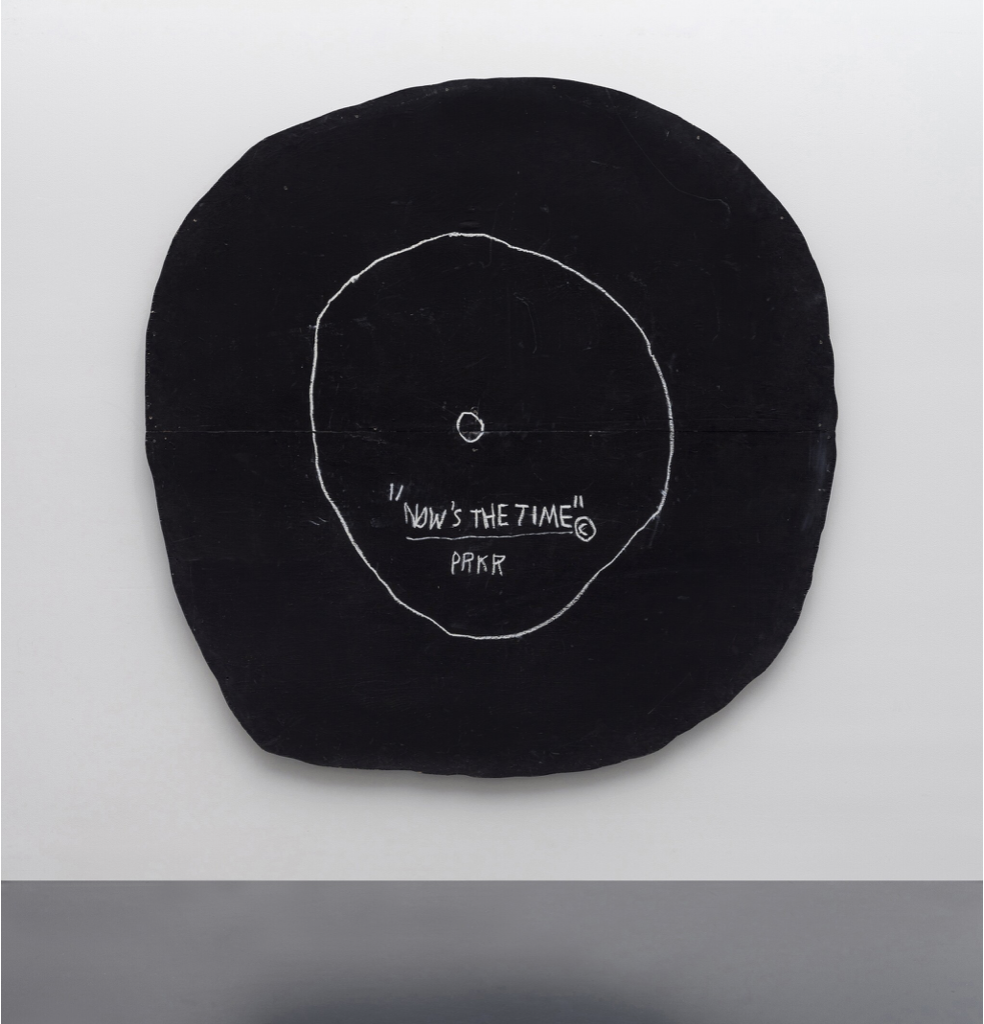

Moore stresses the importance of collecting art books before starting an art collection as a beginner’s guide to preventing hasty purchases while developing personal preferences. He also adds separate reading material on sociopolitical topics such as Race Matters by Cornel West and Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, by Henry Louis Gates Jr. The most distinctive of this list is Kanye West’s Graduation album cover.

Moore’s love and admiration for hip hop culture is evident throughout this book. With hip hop culture deeply ingrained in the lives and bodies of Black individuals, it only makes sense to analyze the influence hip hop culture has on the art market.

Referencing the likes of artists such as Kanye West and Jay-Z, Moore states, “I think hip hop can play a very important role in art, and you see it in people commissioning artists for album covers or people talking about their collections in a vulturous way, saying ‘hey I’m telling you the things that I’m buying, and one of the things that I’m buying is art, and I’m collecting it.’” Reiterating one of his favorite Jay-Z lines, “Twin Bugatti’s outside of Art Basel | I just want to live life colossal,” Moore stresses the importance of showing people how fun collecting art is, which can sometimes get lost in the stigma of owning and collecting art.

Advocating for diversification, Moore expresses the significance of having Black involvement throughout the entirety of his publication process, commissioning Keviette Minor, a Black artist, to design the cover art and Alexandra Thomas, a Black woman, to write the foreward, in addition to interviewing Black advisors and collectors. Moore exclaims, “there’s still a lot of work to be done as far as Black artists getting the respect, attention and access to resources.”

Moore created this book with the Black community and the next generation of art collectors in mind, but he didn’t want to create a book that was exclusive. Aspiring to develop a book that could be enjoyed cross culturally, as an art collector, Moore noticed the disproportionate acquisitions between Black collectors and Black artists, and linked this to the need for a pipeline in art education and accessibility to the youth. Without the “experience of being a second or third or fourth generation art collector,” and inadequate representation in museums, this gap continues to grow. Moore hopes this book will inspire the curiosity of readers to “dig deeper and discover more artists, art books, and galleries themselves.”

Charles Moore is a writer, collector and art enthusiast based in Manhattan, New York.

Kendra Walker (KW): I really appreciate your book, The Black Market: A Guide to Art Collecting. To understand your reasoning behind the creation of this book, can you tell me why you wrote this book and who you specifically created this book for?

Charles Moore(CM): That’s my favorite question, because right off the bat, I want to say I created the book with the Black community in mind. I’ve had some people—white educators and people who are close to me, who have said to me, “This book is great,” and “You could cover up the word Black and anyone could learn from this book.” That was also the look I was going for, that it wasn’t exclusive. I didn’t want to necessarily exclude people from the book, and you notice I don’t say a whole lot of negative things about institutions as far as that’s concerned, but I really wanted to talk to the Black community.

And the reason that I wrote the book is because I am an art collector. I’m pretty involved in the art world, and that can almost be confusing in a sense. You might think that because you’re around all these beautiful Black people in the art world that we make up a large part of the art world, and that’s not necessarily true.

So, there are a couple things that led me to writing the book. I had some conversations with some artists who were frustrated with having Black collectors in their studio for studio visits, people who were certain that resources wasn’t a problem for them. And they would walk out of the studio a little confused, but they would not buy the work.

They also would tell me that the majority of their collectors were not Black collectors, and they had all these Black collectors visiting their studio. So, I would sort of debate with them and say, “Hey listen, maybe it’s because when you walk into a museum, you don’t see a whole lot of Black people in the museum. So, they’re not getting the education, and when they walk into your studio, it’s art 101 for them. It’s not that they had been going to museums for years, it’s not that they have been going to the art fairs for years, it’s not like they have this experience of being a second or third or fourth generation art collector. So when they walk into your studio, you may know they have the resources to purchase the work, but they might be financially resource heavy and knowledge poor.”

That’s one aspect. Then, earlier this year, I was having a conversation with an art advisor, and they were also lamenting that they were dealing with some Black prospective collectors who were also very well off; resources were not an issue. This is a trending topic: Black people are making money, Black people are successful. But what he was complaining about to me was having to explain a lot of basic terms and information to these collectors, who he thought should know this. Like the difference between a print and a painting. He was having to explain these things, and then I started the book in April of this year and finished it in August.

KW: That’s a fast turnaround.

CM: And there’s another interesting thing: “AA.” April/August. African American. And I started it because when we first went into lockdown, I just started reading books including all these books on art collecting, and I started asking some people who had a lot more experience than me in the art world who were friends of mine, if they could refer me to a book like mine. And they kept telling me that it doesn’t exist.

I read all these books on art collecting, and they were wonderful books, but they were written by white males or females, talking about white collectors who collected white art. So I was like, where is the book about the Black collectors who are collecting the work of Black artists? And it didn’t exist. So initially, I started this as just a long essay, and I had no home for it. It was going to be an essay on me going off on why there should be a book on collecting, about Black collectors collecting the work of Black artists. Then I started just going off, and I looked up and I had 50 pages!

KW: [laughs]

CM: [laughs] And I was like, “Oh this isn’t an essay, this is a book for sure.”

One thing that I want to note is that I had Black people involved in every aspect of the book. So, the cover was done by a beautiful young lady named Keviette Minor. She’s a student at USC in her last year. The forward was written by another beautiful Black woman named Alexandra Thomas who’s doing her Ph.D. in art history at Yale. All the collectors I interviewed were Black, and all the art advisors and the students that I interviewed were Black. Every single person involved in the book or who appears in the book, that I personally spoke to, is Black.

KW: I also like your reasoning for creating the book in reference to your thesis about connecting Black students to art museums. It relates to how you’re saying these Black collectors are coming into these studios and it being their first time, without having the complete education behind it because of how rare it is. As you were saying in your thesis, if you grow up, and you’re not exposed to these things, which a lot of inner-city kids aren’t for the most part—maybe a field trip once a year—it makes art more exclusive, and it makes it more uncomfortable. You even said in your book that this was the reason galleries were created the way they are. What do you think?

CM: As far as making the art accessible to Black people, that really boils down to education. You don’t want artists to dumb down their work, but to continue to make work as complex and complicated and filled with layers as possible. Some artists strictly paint realistic work, and that’s beautiful as well. But those artists who are painting and thinking of ideas that are complex and complicated should continue to paint or construct or draw—whatever their medium is. They should continue to do that work as complicated and complex as possible. And we, as Black people, you as a writer, me as a writer, curators, people who work at museums, we have to continue to get our families and friends involved so they have the education.

You casually noted my master’s thesis, and really, what I wrote about is what stymied me from taking my niece and nephews to the museum, with them being pretty much the only Black kids in the museum. And even worse, they live in Detroit. If you want to talk about statistics, Detroit, Michigan has the highest percentage of Black population in any metropolis. 83% of Detroiters are Black. 5% of museum visitors at the Detroit Institute of Art are Black. 5%! It actually might be below 5%.

Every time I’m there with my family (I’m originally from Detroit) I drag my family to the museum, and they know it’s happening, so they hate it. But then they get there, and they love it. Often, they are the only ones there. There might be another Black family—one other Black family in the entire museum—and that’s pretty incredible in a city where 83% identifies as Black. So I really think it’s about the education. I specifically selected the museums I chose in the book at places that have a large percentage of Black people: Atlanta, Detroit, Houston, L.A. I chose those cities on purpose, and I chose those institutions on purpose. They are incredible institutions. You can’t deny that. And we have to pull up.

If we pull up, and we don’t see things that we want to see, then we have to voice our opinion and make our presence known. And the only way that they are going to show the work, collect the art from the Black artist community is if we’re demanding them to.

KW: That is a good segue for this next question. What role do you think hip hop or rap culture plays in the art market, but specifically Black artists?

CM: That’s a brilliant question, and if you noticed, I made sure to sprinkle that into the book, because I wanted to let people know that art is fun. It’s beautiful, hip hop is fun. And hip hop is talking about not just our struggle, but it’s also talking about our success. And art isn’t only talking about our struggle, but it’s also talking about our success and beauty.

I love when I hear any type of hip hop lyric that is eluding to art or artists or collecting, so I started off in the section talking about Art Basel with the Jay-Z line. It’s my favorite line on that particular album from Jay-Z and it’s my favorite line on the song, “Twin Buggatis outside the Art Basel / I just wanna live life colossal.” It just made me think how much fun I had looking at art in Miami at Art Basel.

It’s so much fun, and not just because of the parties. Just looking through the art fair, at beauty and genius, and sometimes you might see Black genius [laughs] and Black beauty. It might be a little rare, but sometimes you might see it. Even in books. I like books. That was also done on purpose: to have an entire chapter dedicated to books, because as I’ve said before, it’s about education, and reading books is important to learning about art. So one of the other things I did in the book was to pick a hip hop album cover.

The nature of an artist doing the cover of this hip hop album—no less a Japanese artist—he’s touching against so many cultures. Japanese culture has been a fan of Black culture for decades. The hip hop artist has also been a fan of Asian culture. So, you go way back to the Wu Tang Clan album, Shaolin Temple, talking about touching down in Tokyo, and feeling like they were Michael Jackson, the way people were responding to their presence. They were just so welcoming and so excited. And this was before hip hop was this mainstream thing, but people in Japan in particular were really embracing the culture and infatuated in a sense with the culture and us as well.

Way back in the 70s and the 80s we loved kung fu and kung fu movies, and all aspects of Asian culture and their beauty is sort of a respectable exchange of culture, I think. I think hip hop can play a very important role in art, and you see it in people commissioning artists for album covers, people talking about their collections in a vulturous way. But in a way, that’s saying, “Hey, I’m telling you the things that I’m buying, and one of the things that I’m buying is art. And I’m collecting it.”

I hate to keep bringing up Jay-Z, but there’s another line that comes to mind where he’s like, “I bought this artwork for 1 million / two years later [it’s] worth 2 million / Few years later it’s worth 8 million / I can’t wait to give [that] to my children.” To me, there are so many layers in that. I know we’re not supposed to be looking at art like an asset and a commodity, but it is. You don’t have to think of it as a stock to trade, but you think of it as part of your net worth, and part of the assets that you hand down to your children. You are not only handing down a cultural asset, but a financial asset.

KW: In the section where you were describing and naming different artists for each decade, who do you think you would pick for the 2000s, because it stopped at the 1990s?

CM: I stopped at 1990 because, well 2000… I don’t know if they were born in 2000. Then they would just be 20 right now. I don’t know if I know anyone that young. I literally just talked to an artist yesterday, and I asked her if there was anything else you think I should know, and she was like, “yeah I’m 22.” [laughs]

KW: [laughs]

CM: That’s important, but even with that, she’s 22, she would make the cut. So I don’t necessarily know that I know anyone that young at the moment. I’m sure there is someone, but even speaking about that section, it was sort of a weird section for me, because I wanted to highlight the fact that there have been artists for a century making art in America. And there is an African American art history.

A lot of the things in the book were like, I’m just gonna sprinkle a little bit on you to arouse your curiosity, and hopefully, you’ll dig deeper and discover more artists yourself, and discover more art books yourself, and discover more galleries yourself, and maybe you don’t live in any of those cities which I selected the museums from. But maybe you’ll say, “I’m in Baltimore, where there’s the Baltimore Museum of Art. I can go there.” So originally, the book was supposed to be the complete list, but it’s not. It’s just supposed to be an introduction to certain areas, to encourage people to explore more.

KW: I feel that if someone were to pick up this book, they would feel more comfortable and confident attending an art fair or going to these specific museums, just having a good reference of what to expect. The way you describe things in your book is very personable, even drawing from personal experiences. What has been the biggest disparity you’ve noticed in the art market since your involvement?

CM: Certain areas are not getting all the recognition. I think there’s still a lot of work to be done as far as Black artists getting the respect and attention and access to resources and things like that. Black artists are sort of having a moment. If you look at the art market as a whole in the U.S., they’re still a very small percentage, which we happen to hear about a lot lately. But I think the biggest issue I have in the art world is everything else.

So I started with the Black collectors. You spoke about my master’s thesis, and I think about the pipeline and the pipeline for the next generation of art collectors, the next generation of art writers, curators, museum employees, people who just like art. When I look at Sotheby’s, and I look at their team (and you can go to their website and look at their entire team) of 300 people who work at Sotheby’s, and then you look at their profiles and its: white, white, white, white, white, white. Look at the editorial team of Artnet: white, white, white, white, white, white.

You often hear these stories about the unicorns. Everette Taylor [Artsy] is the only Black CMO. Why is it always this amazing thing, that there’s one? To me, what would be amazing is someone like Everette being CMO of a major art company, as regular. Because every other position that a white person is holding, we’re not writing about them, about how they’re the only blah blah blah of this company, because there has been all of these others that have come before them.

So, it’s great that we have these pioneers like him and other people, like you, writing about art for prestigious journals. But there has to be more, and if we’re not having more Black writers, Black collectors, Black curators, and Black museum directors and executives and board members and trustees and professionals starting foundations and residencies, if we’re not having that, then that’s an issue for me.

And I think the issue starts with the pipeline. Even one of my readers from my thesis said at the end, “You don’t give a solution,” and actually, I do give a solution. The solution is start the kids early so they know that this is even an option. So many people that I interview who are doing something in the art world were interested in art at a young age, but they weren’t an artist. “I’m not an artist.” They didn’t even know this job existed. It’s like if you don’t know that writing about art is a job, that you could actually make a career out of it. Or that being a curator is a job, you can make a career out of it; like being the marketing person at the museum is an actual career; being a librarian at an art museum is a career. If you don’t even know that those things exist, then you don’t know that that’s something you can aspire to.

Long gone are the ideas that for you to be successful, you have to be a banker or attorney or doctor. That’s the only bar of measurement of success. Because the little white girl who went to Yale and studied art history, and then went to Princeton and got her Ph.D. in art history, and then became the curator of the African wing of the Brooklyn Museum, that was a pretty clear path to success, and that was a pretty clear path to a very prestigious position, and she worked hard for it, and she earned it, but she was told about it, and she was mentored, and she was resourced up and able to study and be trained and be ready for that role. For me that’s the problem.

Make sure when there’s that 15-year-old girl who is looking up to the curator at the Guggenheim, that she looks herself in the mirror and says, that’s what I want to do when I grow up. That she’s able to do it, and she’s able to do it at a high level and is going to be prepared. I remember someone told me they were upset, they were like, “the girl who got that role at Brooklyn Museum? You know, a Black person should have it.” And I said “Well do you know someone? Because we should refer them to that institution, and say, ‘You know Jill or Joe?’”

The biggest disparity I see is the pipeline in education and access for youth, which is the basis of my thesis. Even at the end, I talk about the pipeline. When you expose these young kids to art, it’s not just that they are going to become an artist. Barack Obama said, “Everyone can’t slam a ball like Lebron and have the flow of Lil Wayne.”

And those are really the true unicorns, no matter what color they are. It doesn’t matter that you have to be 6 feet 5 inches. You can’t fake that you’re either 6’5“or you’re not [laughs]. If you’re 5 foot nine, it’s probably not gonna work. I think the opportunity to prop up every other aspect of the art world, and let the writers be the stars and the curators be the stars and the board members be the stars, and stars in all these other aspects of the art world, lets prop those positions up.

Because people study and work hard to be a curator and to write about art, that should be something that someone aspires to be, because they see role models and people they might look up to who are successful, not people who are struggling and doing those highly intellectual things that require lots of work and research for lower, shitty pay.