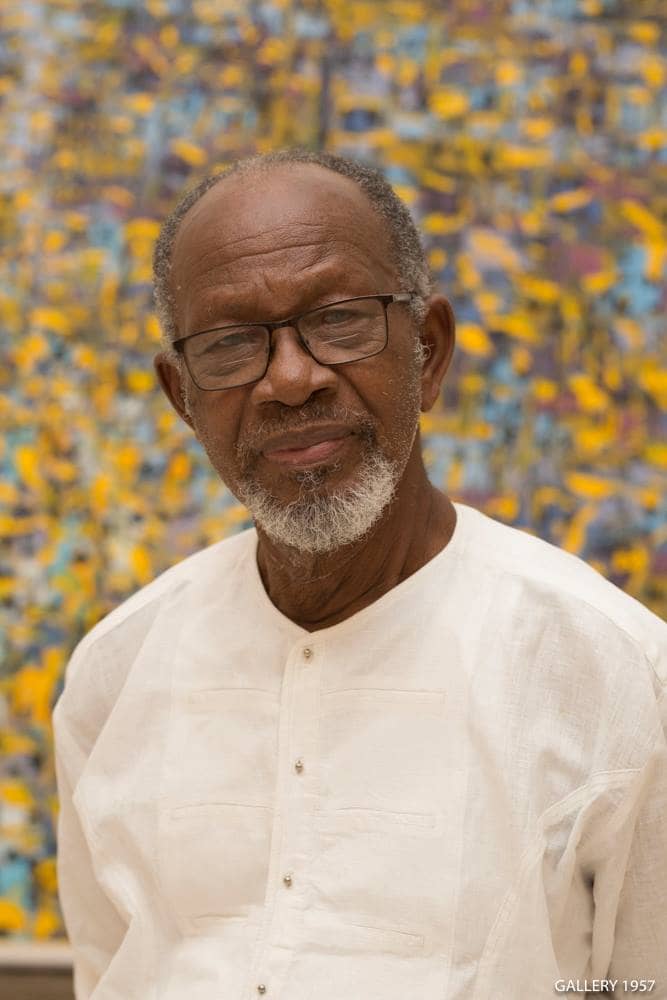

Above: People by Ablade Glover courtesy of Gallery 1957.

At the Gallery 1957 II, paintings made by Ablade Glover hang on the walls of the gallery. The exhibition is a retrospective showing of his paintings made over the last 20 years and beyond, and coincides with the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Artists Alliance, the first modern gallery established in Accra.

Glover, 85, established the Artists Alliance to promote original African arts and provide space for artists. Prior, he had taught at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, where he rose to become the dean of College of Arts.

Even though Glover had been painting since the late 1960s, it was after he retired from lecturing in 1994 that he painted fulltime. In the current exhibition sourced from both Glover and private collectors, the earliest painting is dated 1979.

The exhibition statement quotes Glover as saying

‘I am a child of Ghana’s revolution. I remember as a young boy attending numerous nationalists’ rallies all over the city and hearing our leaders as they convinced people to rise up and seize their freedom . . . These lessons have stayed with me and are reflected in my works’.

Ghana’s revolution is a contention with modernism. Kwame Nkrumah in his 1957 Ghana’s independence proclamation said

‘We are going to demonstrate to the world, to the other nations, that we are prepared to lay our foundation – our own African personality. As I said to the Assembly a few minutes ago, I made a point that we are going to create our own Africa personality and identity. It is the only way we can show the world that we are ready for our own battles.’

In the arts, Kofi Antubam (1922 – 1964), a pioneer of Ghana’s artistic modernism resolved the African personality as a product of transculturation. He wrote in his 1963 book Ghana’s Heritage of Culture

‘One only needs to accept the principle of assimilation as an unavoidable vital force in the development of a people to be able to appreciate the point that the Africanness in the new African personality of the twentieth century cannot be expected to remain what it was from creation. It will have to be a new personality or distinctive identity which should be neither Eastern nor Western and yet a growth in the presence of both with its roots deeply entrenched in the soil of the indigenous past of Africa’.

Antubam’s rendering of the Ghanaian modernist painting includes adaptations of folklore, traditional symbolism and adornments, rejecting the conventions of traditional three-dimensional representation. Body forms are distinctly clear.

While Glover’s paintings maintains the themes that the modernist explores, he largely rejects well-formed limbs and clearly defined body contours in his paintings. Using a palette knife, he gets the freedom to maneuver the wet-to-wet technique, unevenly applies the thick paint in a pointillist manner, expressing in both primary and secondary colours. The paintings presented in the current exhibition falls under Glover’s oeuvre of The Carnival, The People, The Market, Forests cape, Prayers cape and Untitled Series.

Glover has previously described his way of painting as basabasa, an Akan language word for ‘haphazard’. But this is what allows Glover’s The Carnival, The People, The Market and Prayers cape to saddle between abstraction and realism. When you get closer to the paintings you see abstract dots all over the canvas. At a safe distance, however, you see a realist rendition of an African city. Glover relies on the eye to optically mix the dark and bright hues of red, yellow, white, blue, green and the likes of the pure dots into a vibrant, colourful representation of the city.

Accra, the city that Glover was born and bred in, has the destiny of a city and the soul of an informality. Informality means the dots imitate the improvisational characteristics of the city folks. The cityness of Accra has been a constant (re) work of colonisers, post-colonial governments, indigenes and out-of-city settlers. The paintings offer aerial views. It is as though the paintings are trying to map the contestable space of the city. According to Marxist urban theorists, cities are both ‘a symptom and a producer of social relations’. When you see the paintings, you ought to think about power relations, inequalities that living in the city affords.

The People is red and yellow paintings of a conglomerate of people placed side by side on the wall of gallery. Even though the outlines of the figures can be seen, they remain faceless. In a democracy, what does it mean to say ‘We the People’? Are the masses without (political) power even when they vote?

The Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye contends in ‘We the People’: In Praise of the Politics of Inclusion that

‘People want to feel, surely, that they are involved in the decisions of the government, that their ideas and opinions matter and, if equality means anything, should be of the same weight as those at the helm of affairs who were elected by them.’

In the paintings, the people go about their normal duties with their innocence and sometimes, naturalness. Are they actively aware of their power (lessness)?

The Prayer series is a mass of Muslim congregation on their knees, praying. The paintings are rendered in four different colours and hung in a square formation. It seems the prayer is taking place in the open, rather than in a mosque, a testament to improvisational nature of the city folks. But in this improvised prayer place, there is no gender partition. Or is it that those praying are of one gender?

The market is a dynamic place in Ghana’s culture. It is not only for trading the legal but also, the illegal in wholesale and retail businesses. In 1979, Markola No.1, the chief market in Accra, was destroyed by the government. The market women were accused of hoarding commodities and/or selling above authorised prices, a phenomenon that came to be known as Kalabule. These were seen as economically sabotaging the government by instigating shortages. The women were also seen also wealthy people who funded coup and counter coup d’états. The destruction of the market was deemed to strip the women off their economic power. Often, market queens were at the full blunt of the violence.

The market scenes seem to be Glover’s memory of the lost years of Markola. In the series, there is a modernist, realist rendering of three market queens. It is their strength of triumph that keeps them going. At the face of systematic oppression by the state, the women still rise.

What holds Glover’s pointillist paintings of the city is movement, mobility. In contemporary times, we invoke Accra we dey to mean that in order to survive in the city, you have to hustle, hustle hard. The faceless masses are on the move in the paintings, trying to survive.

In the Forests cape are brightly coloured trees. The scenes are devoid of human presence. The viewer comes into contact with serene environments, nature undisturbed. What would the city have been without the occupation of human beings?

Through these paintings, Glover transmits his memory and vision of Accra to us. They serve as soundtracks to visual histories. The paintings remind us of how the city has been, and how to live in the city.

Prof. Ablade Glover: Retrospective

Gallery 1957, Accra, Ghana

23 January – 27 February, 2019