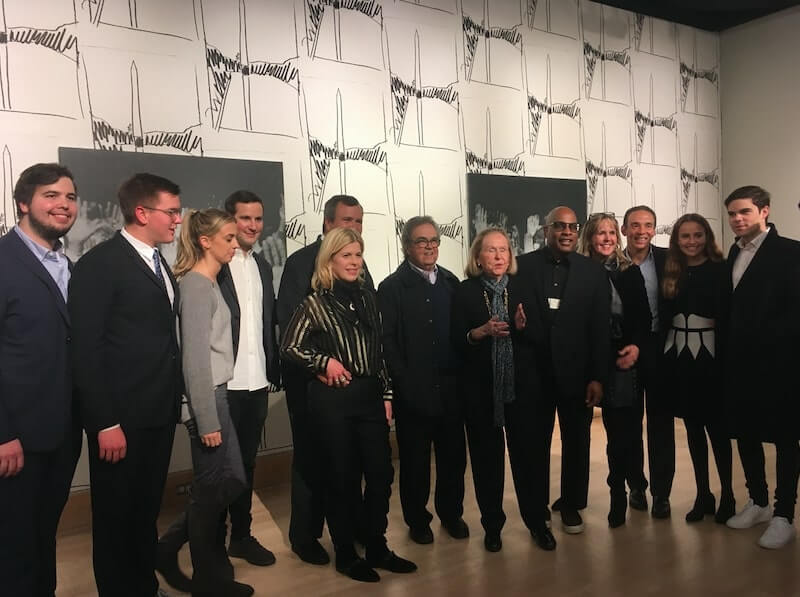

Above: Glenn Ligon and the de la Cruz family. Photo by the author.

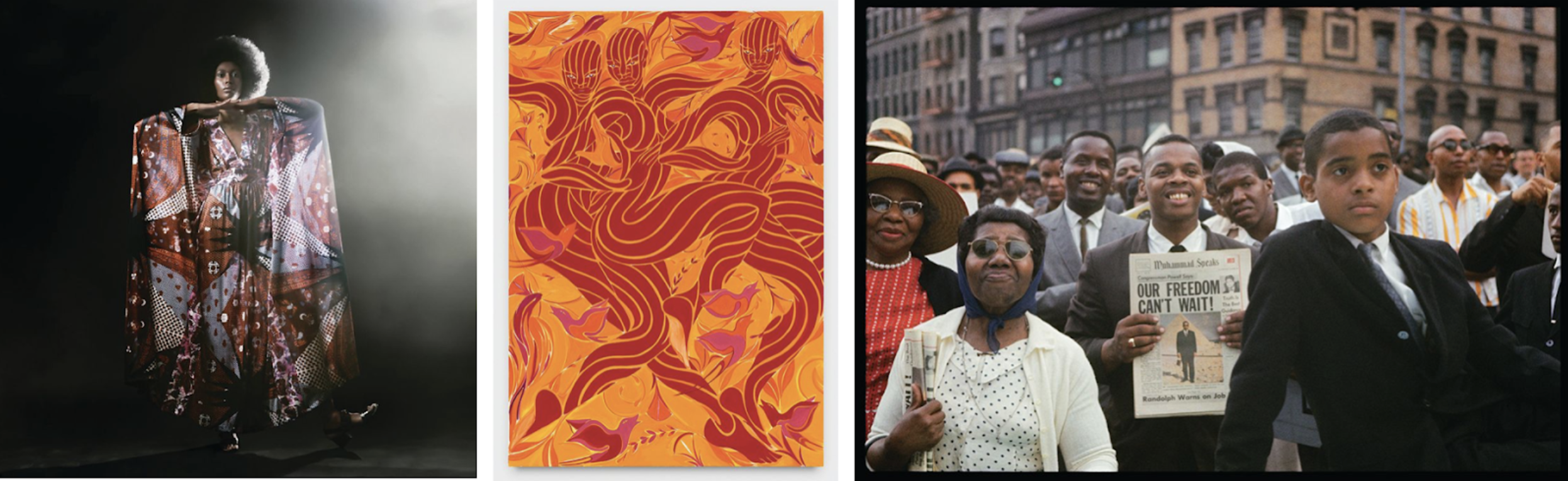

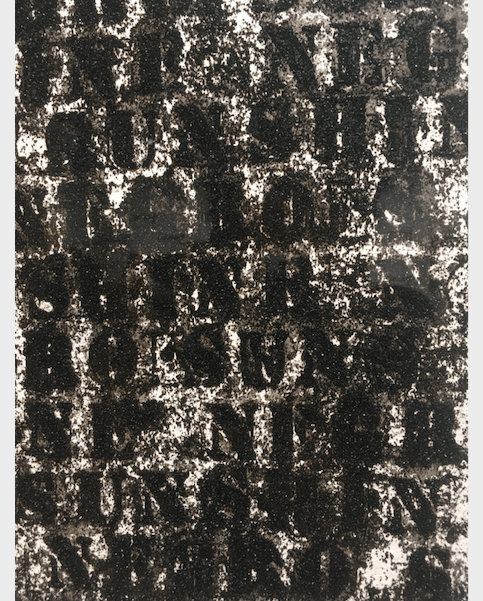

On January 24, 2019, Glenn Ligon opened a solo show at the newly constructed Maria and Alberto de la Cruz Gallery at Georgetown University. The audience included notable collectors and artists from both D.C. and Miami, where the de la Cruz family live for most of the year and have a 30,000 sq ft collection in the Design District. In D.C., Ligon took inspiration from writers James Baldwin and Gertrude Stein for the displayed silkscreen and applique pieces. The decade-long Study on Negro Sunshine series (2008-2018) literally disintegrate particles of the written word into a void of white and red; the larger artworks, Grey Hands (1996), are disembodied limbs that only slightly change from one canvas to the next.

Ligon used Andy Warhol’s rarely exhibited 1974 screenprint of the Washington Monument as a wall-paper to the Grey Hands canvases in the show; the pairing created yet another dialogue between past and present, from one form of reproduction and repetition to another. The ongoing struggle for visibility is the inspiration for the title and theme of Ligon’s show, To be a Negro in this country is really never to be looked at.

While talking to Ligon, I started to compare the racial theme of the March on Washington in 1963 and the Million Man March in 1995 to the more recent context of the Women’s March in DC:

Lyric Prince [LP]: In your wall text, you refer to the Silent March and the March on Washington in 1963, and particularly focus on Louis Farrakhan’s role in organizing 1995’s Million Man March with Grey Hands (1996). This year, the Women’s March co-founder Tamika Mallory publicly supported Farrakhan, which alienated her from the rest of her associates. I’m struck by the fact that she’s seemingly choosing Blackness over her womanness in terms of equality. How can you pick and choose your battles? I don’t know if you have any commentary on that.

Glenn Ligon [GL]: I don’t actually know much about the debates around the Women’s March in particular; just things that I’ve read online. That’s just the lesson of intersectionality. I just would say that…in reference to earlier marches, this trope of visibility and Black invisibility has been played out in symbolic marches in Washington for a long time. So, I’m interested in history, but I’m also really interested in why we feel the need to assert our presence over and over again, in these highly symbolic, charged spaces when we’ve been here from the beginning. But, I’m also interested in … the repetition of images; from the wallpaper and from the paintings themselves.

LP: It’s the same thing, always.

GL: That same thing, same AND different because each painting is different. They shift the scene that’s being depicted, from painting to painting.

LP: But then you speak to the anonymity; how each scene is different, but it has that same feeling of, “why are we here?”

GL: Which isn’t to say that the historical circumstances are all the same, but it is to just think about the kind of return of [those same themes]. And if you think about the Black Lives Matter protest, the raised hand is used in another way. Hands up, don’t shoot.

LP: Yes, that’s right.

GL: So, that’s part of this, in a way. Grey Hands is about this kind of connection historically between these various moments.

LP: Also, gray is this very neutral color.

GL: You know, part of it is because these were images from magazines and newspapers, so they allude to that, but also, yes. Gray is this sort of, you know, funny color.

LP: It’s not white! It’s not black!

GL: Yes! [laughter] Because often I think if they were in black and white, they would get read too quickly in these kinds of racial binaries.

LP: How do you choose your themes? You have Baldwin and Gertrude Stein in this conversation with each other. I feel like Stein had these really interesting stereotypes with the Black woman that she was describing in some of your pieces. And then you have Baldwin talking about invisibility under his Black skin with your show’s title. How do you connect those?

GL: The conversation is about repetition. Again! Also, perception and language. You know, Stein’s novella [Melanchta] has very contradictory descriptions of her characters… even though one could say, just on the face of it, that they’re just a racist kind of description. But they’re so complex in the way she keeps describing the same characters over and over again, and you’re never quite sure what she thinks or what they mean. So she describes the character Rose as a “real dark negress,” but then she was brought up by white people.

LP: It’s a juxtaposition, right? That you’re human, but not?

GL: Well, it’s those that make her whiter, because it’s this juxtaposition of racial categories and environment. Then [Stein] says her laughter is not like Black laughter-it’s like any other woman’s laughter- but suddenly Blackness as a category is different from womaness. Clearly what she means by any other woman is any other white person, you know [laughter]? So, it’s a very complicated thing she’s trying to do with it. And I became interested in that; but also interested in this- in a way- ridiculous juxtaposition of ‘negro’ and ‘sunshine,’ because they are set up as opposites.

LP: It’s kind of like…

GL: Light and darkness, mapped onto racial categories, which is, of course, what [society] has always done with Black people!

LP: When you use Gertrude Stein’s text, you’re applying this creative interpretation with the reality of a Black woman being in a white space, and the limitation Stein is facing basing her fiction off of what she perceives to be the reality of how Black people act. It’s more likely a portrayal of a false sort of face.

GL: I don’t know, it’s code-switching! I mean, we’re different in every kind of space we occupy. Zora Neale Hurston, which I’ve used a lot, has a work called, How It Feels To Be Colored Me. She talks about being one of the few Black students [at Barnard.] And one of the sentences in the essay is, “I feel most colored when I’m thrown against a sharp white background.” So it’s that context makes her blackness more pronounced, apparent. She feels it more, you know, but then there was another sentence in the essay where she says, “I do not always feel color.”

One of Ligon’s long-time admirers, Bonnie Clearwater-director and chief curator at NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, FL-told me about the longstanding struggle for artists of color to obtain visibility in the elitist world of high art:

In San Francisco, in the late eighties, the city government threatened to withdraw money for the cultural institutions if they didn’t become more inclusive. It might look like suddenly there’s this great interest in black artists, but there has been a growing emphasis on recognition and greater exposure for a long time… [A]rtists such as Glenn, Mickalene Thomas, Rashid Johnson, now have clout in that they can recommend that galleries, curators, or collectors to look at the artists from earlier generations that were their mentors…or to look at the young up and coming artists. Consequently, there is both a looking back and looking forward that’s making it [seem] like there is currently an unparalleled expansive pool of artists, but they’ve always been here; [just without] widespread recognition.

In the struggle to be seen, Ligon makes the forceful point that presence does not always translate to being truly present in other people’s consciousness. In his show, there is an ongoing tension of using a Eurocentric environment (represented by Warhol’s wallpaper) and the “proper” use of English language to both assert and challenge the erasure of Black people in America. With his focus on the mendacity represented in Grey Hands and symbolic marches and the repetition of crumbling letters that fail to capture the essence of their main subject in the Study for Negro Sunshine series (2008-2018), Ligon conceptually raises the bar in Black art.

Through his characteristic restraint of color that contrasts with the textural feel and content of his work, Ligon tries to show viewers the blur of class, identity and sense of place that African-Americans- and the LGBTQ community- experience in mainstream society, and the various modes of protest in an ongoing conversation. It also asks something unknowable-do they even matter in the long run? Ultimately, Ligon’s show demonstrates how the white gaze plays a similar role with the gendered one, that looks at their subjects with curiosity but no real understanding.

Glenn Ligon: To be a Negro in this country is really never to be looked at will run from January 24 through April 7. To learn more about the exhibition and events at the gallery, please visit https://college.georgetown.edu/collegenews/ligon-exhibition-opens-at-de-la-cruz-gallery