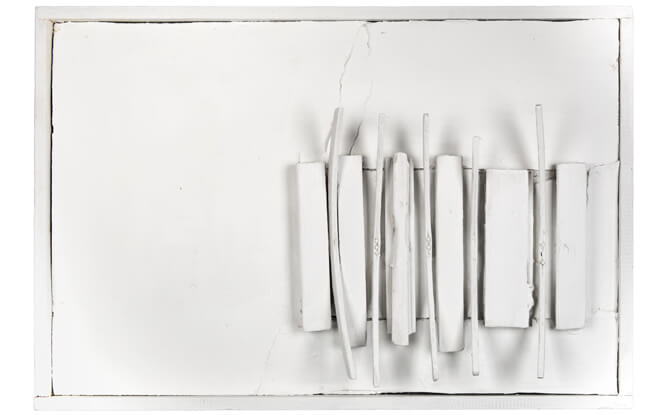

Above: Mildred Thompson, Wood Picture 4, ca. 1967; Found wood and paint, 25 1/2 × 38 1/4 × 2 3/4 in.; New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Leah Chase Fund, 2016.50; © The Mildred Thompson Estate, Atlanta Georgia. Photo: TK

Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, the 1960’s to Today, on view at the National Museum of Women in the Art, illustrates the power of believing in a reality that is beyond what we see every day while leaping outside of the externally-imposed box of Black Art. One of the first high-profile surveys of Black Abstractionism, the show explores these questions, through its very existence: What does it say about our society, that these uniquely talented artists needed to band together to be better seen? Also, how does a show like this illustrate the growing inclusiveness of the art world, as well as its need to expand the geographic and social reach of its audiences? The answers to either one of these questions lie in our perception of the show, its placement in two prominent collections started by independently wealthy women, and how we feel about the roles and actions of Black Women in art world itself.

As the title suggests, each work of art pulls towards and supports each other.

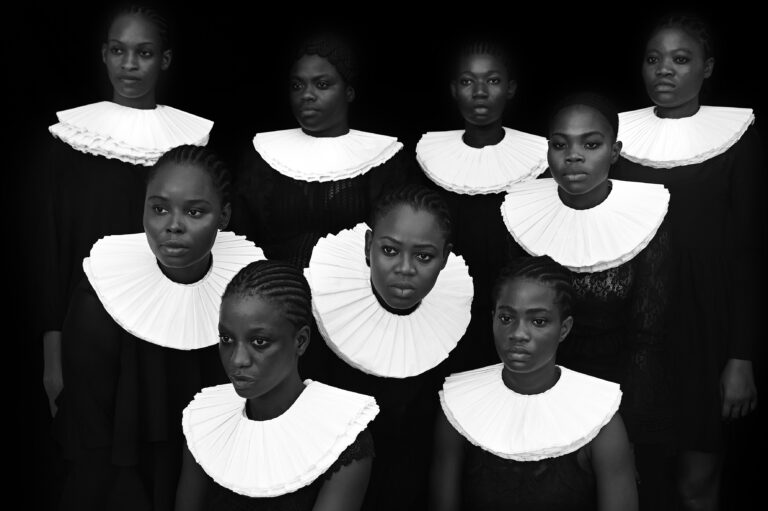

It is a show of textures, where the smooth and the rough illustrate all shades of Black. There are glossy mountains of cadmium orange, next to ultramarine swirls, celebrating familial love (Snowden, “June 12, 1992”). Plastic parts and scent jut from a solid black base, probing at negative space (Booker, “El Gato”). Fragile newspaper nests form from mass media accounts of Black pain, exclusion, and death (Hassinger, “Wrenching News”). Also, the viewer can connect with the shapes and symbols of Africa, reclaimed from the Cubists that plundered it (Pusey, “Deyjgea”). In particular, this piece has the sharp edges and clarity of color that reveal the inner order and strength necessary to survive and thrive in spite of misguided expectations, and its geometric composition reflects emotional balance and logical placement.

This group forged its path by ignoring the outside world’s desire to bind them to fetishized black forms and forgoing the approval of the white male gaze. Sex is reinvented into the symbolism of soft curves, edges, and folds of textures. Within every stroke and shape, one can see that the artists took their freedom wherever they could find it, and ultimately, it’s something realized, rather than given or earned.

The abstractionism within this show breaks down the recognizable stereotypes of mammy and Sambo into something more, taking control of image to reconfigure them into the free expression of civil rights. Each piece shows, rather than tells, the complicated inner life and vision of their creators, challenging the implied foothold of privilege within abstract art, and expands the boundaries of that form to include anyone, of any gender or color, who can hold a brush.

The curators, Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina, are white, but played a crucial part in helping the featured artists give birth to the concept and production of this show. They, in tandem with the support of the Kemper and NMWA, appear to have real love and respect for all the artists involved. More importantly, they are conscious of the fact that Black women have served as the surrogates of American culture for too long, while America has also birthed the current identity of Black women. With the creation of this show, we potential in how this social contract of oppression can be renamed as inclusion.

Reparations, a word that dates back to the Reconstruction, can be the keyword to the idea of Magnetic Fields itself: its original connotation of recognition has been reclaimed. The Kemper and NWMA joined forces with the artists, combining their missions of activism and art efficiently; also, displaying the works gives greater recognition to the hosting institutions themselves, both located in places not necessarily known for their artistic output. Missouri, with its agricultural and homogenous community, needed exposure to different perspectives and persons of color, while D.C. afforded the exhibition greater political legitimacy by its placement, as well as public access to Magnetic Fields’ many D.C.-based artists themselves.

To better serve the artists and the educational prospects of the exhibition, the curators connected with those who supported these women’s careers throughout the years. ”[We] reached out to scholars [and] curators of color to create a panel of everyone who has written incredible scholarship about [Black women] artists’ work,” as a means to select the best pieces for the show, Messina explained. Together, they selected the exhibiting artists, who span a century of ages (Alma Thomas, the oldest artist, was born in 1891; Abigail DeVille, the youngest, came to be in 1981). Multiple generations of daughters who became art mothers, teachers who were students, create a magnetic continuum of excellence and pure expression. And so, the artists in Magnetic Fields reclaim their birthright and place in the future; additionally, the curators and institutions that are involved seem eager to share space and support to move us all forward. Ending the cycle of supremacy is freeing yet frightening, making us break each other chains when we can no longer break our own. Lilian Thomas-Burwell, the living artist emeritus of the show, spoke on sharing inspiration with her cohort of abstract artists and admirers. “Everyone has an important something, hidden, that they can’t recognize in themselves,” she started. Burwell paused for a bit, beamed up at the audience, and finished her observation-“And we can’t see that light [inside] until it’s plugged up.” And through this light, we see that we are one, or we are nothing.

Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today on view October 13, 2017–January 21, 2018 at the national Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C. . Purchase tickets here.