This summer, Pérez Art Museum Miami ( PAMM) featured a screening series of the work of Black Audio

Film Collective, the pioneering group of British filmmakers and artists whose work in the 1980s

and 1990s continues to stand as a touchstone in black cinema, thanks to its exploration of

issues of identity, representation, and social and civic oppression of diasporic peoples in

Thatcher-era Britain. It’s a filmography that emerged from a historical moment with parallels to

our own, marked by a political drift to the right, uncorked racial tension, and strong anti-immigrant fervor.

Fittingly, the series commenced on July 6 with a screening of director John Akomfrah’s debut

documentary Handsworth Songs, the first work produced by the collective. Upon its debut in

1986, the film won several plaudits for its exploration of the landmark 1985 Handsworth riots in

Britain and established avant-garde techniques which would come to be associated with BAFC:

tableaus of still images and re-stagings of remembered moments, remixed archival footage, and

fractured narrative, all of which, when taken together, present an artful approach to the subject

matter that often feels like an investigation as well as a fever dream.

The screening was introduced by Yesomi Umolu, Exhibitions Curator at the Reva and DavidLogan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago. Born in Lagos, Nigeria and raised in

London, Umolu’s training, and career began in architecture but developed into a curatorial practice informed by her work in museum education and public programming. Umolu’s practice draws on her own multicultural and diasporic background, showcasing the breadth of global contemporary art and spatial practice.

The series concludes on Thursday, August 10th with a double bill of Akomfrah’s Last Angel of

History, and Memory Room 451. To give context to the series, I spoke to Umolu

about the BAFC, and just what makes the collective so important.

Jason Fitzroy Jeffers (JFJ): How did you come to the work of BAFC?

Yesomi Umolu (YU): Black Audio is a very seminal collective within the UK context. Anybody studying visual culture, art history or curatorial practice sure comes across their work. BAFC speak to a defining moment in the 1980s when Britain was experiencing its multicultural awakening. BAFC stood out because that was a group of young, Black and South Asian practitioners who mobilized their artistic production to addresses questions of discrimination and representation in the UK.

I was recently in London, and I saw the exhibition “The Place is is Here” at the South London Gallery, which showcased works by other artists and collectives that were active at the same time as BAFC, including the Sankofa Group, Gavin Jantjes, Lubaina Himid, Rasheed Araeen and others.

JFJ: You mentioned these other collectives and artists who, to audiences over here, might not

be as well known as BAFC. If and how does BAFC stand out amongst this pack?

YU: Artists develop at different stages, and the timeline for their recognition by the mainstream art world can vary greatly. In my view, BAFC has gained a lot of visibility because of the strength of their collective vision and the innovations they made to the essay-film genre.

I would encourage everyone who takes an interest in their work to read up on the history of

black British art because it becomes clear their practice didn’t evolve in isolation, and it was indebted to a rich set of critical conversations that were happening in the UK at that time. It is incredible to think about the contributions made by BAFC peers including Isaac Julien whose work attended to questions of black masculinity and sexuality, as well as the scholarship of Eddie Chambers and Rasheed Araeen who were instrumental in making exhibitions and writing about this generation of artists. I would say that while the output of Black Audio Film Collective is exceptional, they are part of a larger story that is only just beginning to gain widespread attention outside the UK.

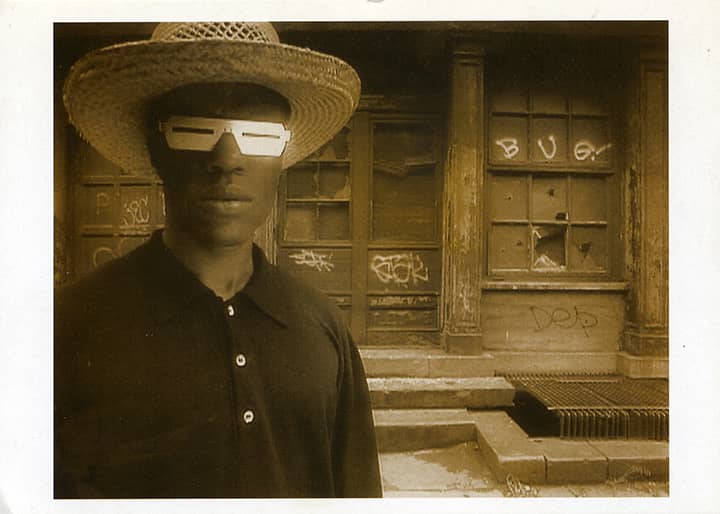

Above: John Akomfrah, The Last Angel of History, 1995 Digital color video, with sound, 45 min., 7 sec.

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

JFJ: Watching these films, I’m struck by how much they resonate with the present; Reece Auguiste’s Mysteries of July explores unexplained deaths of black youth at the hands of the police, and it’s hard not to think of events in Ferguson when watching Akmofrah’s Handsworth Songs. We’re also staring down the anti-immigrant rhetoric of Donald Trump and Brexit in the UK. These particular films were made in the mid-80s, and yet the themes feel even more relevant now. It almost seems like history is repeating itself.

YU: Having come of age in the late 90s and 2000s, my generation benefited from the hard won fights of the the 80s and 90s. I grew up at a time when multiculturalism was greatly celebrated as being part of British identity, not solely as an ideology, but as something that was put into practice through national policy. This trickled down to the work of institutions who made strides to be more representative, promote social mobility, and expand on the narratives and histories that were visible in cultural spaces. It is important to acknowledge—though it may seem like history is repeating itself— that there’s always change and progress, however minute. Progress benefits someone somewhere, and this is something that we can come to celebrate. I have certainly benefited from the work of BAFC and their peers.

Things perhaps happen cyclically, and while we make advances at a higher rate in one area, we

might have to take a couple of steps back in another to move forward in another area. I

would like to think that this moment in history is that and that we’re in fact contending with the residues of things that have always existed. Whether fighting for representation or democracy, there is no ultimate utopia but rather the constant pursuit of it.

BAFC’s work may be timely now because it seems that we are living in times that resemble the 1980s and 1990s, but things have inherently changed. I think that where John and his peers were achieving many firsts and gained a level of traction that hadn’t been witnessed before, today we have multiple voices addressing these issues, and they add to a great tradition of art that responds fervently to the politics of its time.

It’s becoming increasingly important today that we recognize the work of Black Audio Film Collective and encourage a new generation of artists to follow suit. This is what makes the screening series at PAMM so crucial.

Jason Fitzroy Jeffers is a filmmaker, writer and musician from Barbados who lives in Miami. He is the co-founder of Third Horizon, a Miami-based collaborative of Caribbean filmmakers whose work has been featured at Toronto International Film Festival, Sundance Film Festival, and others. He is also Festival Director of the collective’s Third Horizon Caribbean Film Festival, an annual showcase in Miami of cutting-edge Caribbean cinema.